Communist China – Part 2

China’s communist political system

Continuing this essay series on communist China, using Arthur Kroeber’s China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know, Michael Pillsbury’s The Hundred-Year Marathon: China’s Secret Strategy to Replace America as the Global Superpower, Chris Miller’s Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology, and Elbridge Colby’s The Strategy of Denial: American Defense in an Age of Great Power Conflict, this essay will focus on China’s political system.

As Kroeber writes:

China’s political system is unusual, perhaps unique, in combining a high degree of formal centralization and actual decentralization. In theory, the central government in Beijing, controlled by the CCP [Chinese Communist Party], sets all policy, controls tax rates and revenues, and guides the economic ship. In practice, local governments at the provincial level and below have enjoyed great latitude in adapting (or even ignoring) central policies, setting local development priorities, and encouraging local businesses. This de facto decentralization enabled bottom-up local entrepreneurship to thrive and saved China from the rigidity and inability to adapt that doom centrally planned economies. But the central government’s effective control over key economic levers, through the financial system and nationally organized state-owned enterprises (SOEs), meant it could build out critical national infrastructure far more rapidly than is usual in really decentralized countries … [But] over the past decade—and especially since Xi Jinping became China’s leader in late 2012— … [i]nstead of … steadily increasing the role of the market, officials now stress the need for “top-level design” and a high degree of state ownership. The Communist Party increasingly tries to influence private firms through party committees embedded in companies. Access to China’s market for foreign firms remains far more tightly restricted than in most advanced economies. An industrial policy initiative launched in 2015, “Made in China 2025,” includes specific targets for the amount of market share Chinese companies should take from their foreign rivals in technology-intensive industries. This initiative is backed by hundreds of billions of dollars of state subsidies. Finally, China’s rapidly growing international investments—notably through the “Belt and Road” global infrastructure program announced in 2013—are spearheaded by state-owned construction firms and banks.

The CCP is structured much differently than the former Soviet communist party. As Kroeber writes:

The important thing is not the obvious fact that the Communist Party is in effect the sole legal party but rather the nature of the party. Rather than a tiny cabal of secretive leaders, it is a vast organization of some ninety million members (more than 5 percent of the nation’s population) that reaches into every organized sector of life, including the government, courts, the media, companies (both state-owned and private), universities, and religious organizations. Top officials in all these organizations are appointed by the party’s powerful Organization Department. “A similar department in the US,” writes journalist Richard McGregor in his book The Party, “would oversee the appointment of the entire US cabinet, state governors and their deputies, the mayors of major cities, the heads of all federal regulatory agencies, the chief executives of GE, Exxon-Mobil, Wal-Mart and about fifty of the remaining largest U.S. companies, the justices on the Supreme Court, the editors of the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and the Washington Post, the bosses of the TV networks and cable stations, the presidents of Yale and Harvard and other big universities, and the head of think-tanks like the Brookings Institution and the Heritage Foundation.” The party no longer tries to control the minutiae of every individual’s life, as it did during the Maoist era, but it does seek to directly control or heavily influence every sphere of organized activity.

As Pillsbury similarly writes:

Owing to pre-Communist Chinese civil-military traditions dating to about 1920, high- ranking Chinese military personnel are expected to play a significant role in civilian strategic planning. To get a sense of just how different this is from the American system, imagine that issues that are generally considered to properly fall under the purview of U.S. civilian leaders, such as family planning, taxation, and economic policy, were instead transferred to generals and admirals in the Pentagon. Imagine further that the United States lacked both a supreme court and an independent judiciary, and you get some sense of this tremendous disparity between the relatively narrow influence of our military leaders and the broader advisory role played by China’s top military leaders since 1949.

This structure has been run differently over different time periods. As Kroeber writes:

Under communist rule, China has experienced several different governance styles. Mao Zedong ran China essentially as a personal dictatorship from 1949 to 1959 and again during the Cultural Revolution of 1966–1976; in between, power was held by a bureaucratic elite that tried to govern in a more collective way. Deng Xiaoping was a key figure in this bureaucratic elite; after he became the country’s paramount leader in 1978, he designed a bureaucratic-authoritarian system of “collective leadership” specifically to prevent the reemergence of a dictator such as Mao. This system endured at least until 2018, when Xi Jinping changed the constitution to abolish term limits for state president, enabling him to serve indefinitely as China’s top leader. Along with Xi’s other moves to concentrate virtually all decision making in his hands and to establish a cult of personality around himself, this suggests that China is moving back toward dictatorship.

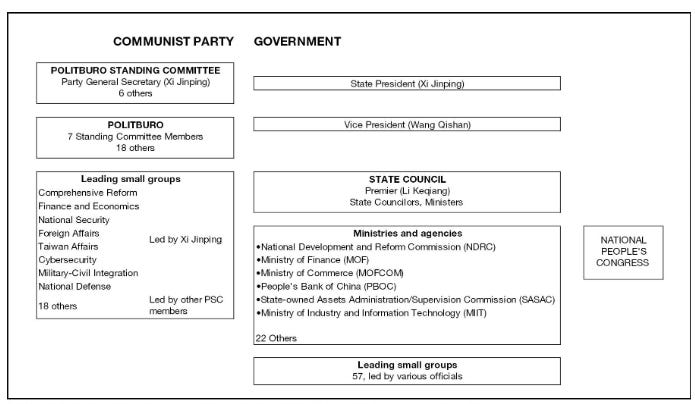

At the top of the pyramid of Chinese power sits the standing committee of the party’s Politburo. This group, which at present consists of seven members, is the nation’s core leadership, and the most important decisions require consensus within this group—although of course the views of the top leader carry a lot of weight. The standing committee sits inside the broader, twenty-five-member Politburo, which meets several times a year and ratifies many major decisions. Next in line below the Politburo are the “leading small groups” (LSGs), which the party and government organize to coordinate policy on major issues. Membership in these groups typically includes a range of officials holding government or party posts in a variety of agencies.

How do Chinese leaders manage the trade-off between economic growth and political control? As Kroeber writes:

Liberal analysts both in the rich democracies and inside China observe that virtually all of the world’s richest countries have democratic, or at least relatively open, political systems. They also observe that authoritarian regimes eventually tend to put their own survival ahead of the economic welfare of their citizens. Many conclude that China’s leaders will ultimately be forced to choose between opening up their political system or keeping a grip on power and letting the economy wither. Chinese leaders continue to reject this choice, so far with success. Xi Jinping tightened political control, while still achieving average annual GDP growth of 7 percent in 2013–2018. But of course many individual economic reforms require the state to give up some power. Streamlining the SOEs means a big reduction in the state’s ownership of assets. Financial liberalization means cutting the government’s ability to direct capital to its favored projects. Enabling a dynamic Internet risks giving citizens new channels to criticize the government. The enduring dilemma of party-driven economic policy is how much and what kind of power are Chinese leaders willing to sacrifice in exchange for how much and what kind of economic growth? … As China tries to move to become a more consumer- and innovation-driven economy in the 2020s, further erosion of state controls may be required. Yet rather than signaling more openness, Xi Jinping has moved in the opposite direction: he has strengthened the central state’s control over localities and moved China closer to a personal dictatorship. These moves put at risk the flexibility that has made the Chinese system more resilient and successful than other authoritarian states.

Kroeber then describes this more recent authoritarian approach:

The Third Plenum Decision was a lengthy document signaling the main directions of Xi Jinping’s economic policies, without getting into much operational detail. It contained two core and apparently opposed ideas. The first was that market forces would play a “decisive” role in resource allocation, an upgrade from the “important” role assigned to the market in previous party documents. The second was that the state sector would retain its “dominant” role in the economy. This seems like a contradiction. If market forces were truly decisive, the dominance of the state sector could not be guaranteed: state firms might lose out to private ones in market competition. Conversely, if state dominance were guaranteed, market forces could not be truly “decisive.” Chinese leaders see no paradox in their embrace of both a “decisive” market and a “dominant” state. State enterprises are crucial because they enable the government to pursue strategic development objectives and to intervene to stabilize the economy when times are tough. (Stimulus via state-led infrastructure spending was a big reason why China weathered the global financial crisis of 2008–2009 so successfully.) At the same time, the risk of waste and inefficiency in SOEs is high, so they must be subjected to market discipline to ensure that they remain reasonably profitable. One way to think about it is that market forces are indeed “decisive” much of the time—until they threaten the “dominance” of the state, at which point they are curbed. In practice, this means that markets generally determine the prices of goods and services; but they are not allowed to transfer control of assets from state owners to the private sector.

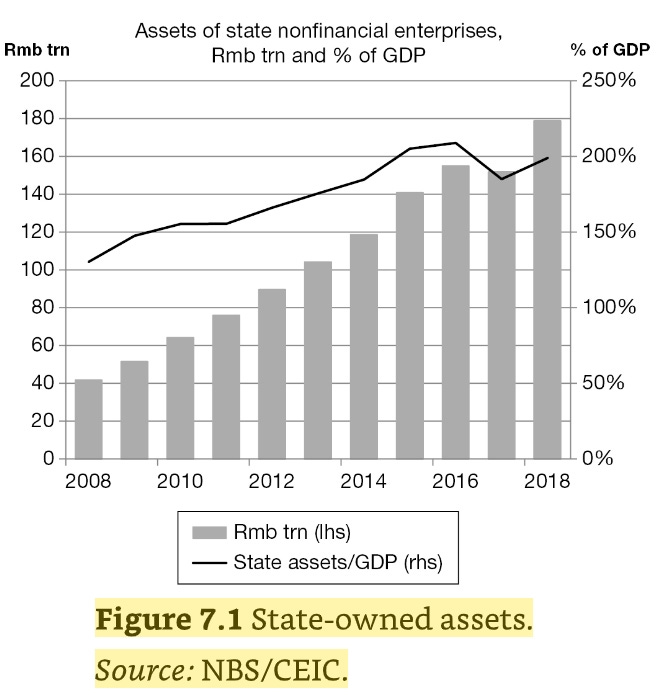

China’s economy is still dominated by government-run enterprises. As Kroeber writes:

China remains an extraordinarily state-dominated economy in which SOEs [state-owned enterprises] command a far larger share of national assets than they do in other countries, and the vast majority of large firms in almost every economic sector are state-run … [P]rivate firms are, on average, small. The overwhelming majority of the largest companies in China are state-owned, and state firms dominate most capital-intensive sectors. The state sector’s share of national assets is far larger than in any other major economy.

As Pillsbury writes, “[SOE’s] control numerous economic sectors, and are major players in seven strategically important sectors: defense, power generation, oil and gas, telecommunications, coal, aviation, and shipping. China’s leaders can direct the SOEs with subsidies from massive foreign exchange reserves, so targeting foreign markets will be far more common. From 1985 to 2005, China spent $300 billion to support the largest publicly owned companies. Their access to cheap capital and underpriced inputs is notoriously unavailable to their international rivals, and they are aggressively increasing their outward investment.”

But the CCP has released its grip on enterprises that manufacture and sell more run-of-the-mill products and services:

[A]doption in 1995 of a comprehensive SOE reform program, under the slogan zhuada fangxiao (“grasp the big, release the small”) [was based on] [t]he basic idea was that there was a host of industries, such as consumer goods manufacturing and basic services such as retail shops and restaurants, where state ownership was unnecessary. Small-scale SOEs in these sectors (most of which were controlled by local governments, not the center) could be privatized or bankrupted, and these economic areas could be handed off to the private sector. But state control of what is sometimes called the “commanding heights” of the economy needed to be strengthened. These “commanding heights” included: Important national networks, including aviation, railways, telecoms, and power generation and distribution; Upstream production of oil, gas, and coal; Basic heavy industries such as steel, aluminum, and petrochemicals; Production of critical heavy machinery such as machine tools and power generation equipment; Infrastructure engineering for the construction of roads, dams, ports, and railways; “Pillar” consumer durables industries, notably automobiles; and Military equipment. Under the zhuada fangxiao reform, state ownership of these commanding-heights sectors was organized under large-scale business groups controlled directly, in most cases, by the central government … The biggest Chinese SOEs are very big indeed, and the vast majority of really large companies in China are state-owned. In 2018, 103 mainland Chinese firms appeared in the Fortune Global 500 list, which ranks the world’s biggest firms by revenue. Of these, 67 were central SOEs and another 20 were local government SOEs. Only 16 were private firms. Since the conclusion of the zhuada fangxiao reforms in about 2005, state firms have rarely gone bankrupt or been taken over by more efficient private competitors. Since 2009, Beijing has encouraged SOEs to bulk up their assets and has allowed them to take on enormous debt to support their unprofitable investments. SOEs may not be monopolies, but they are certainly insulated from competitive pressures, and their decreasing efficiency is taking a toll on economic growth. About 40 percent of state firms do not earn enough profit to cover their cost of capital, meaning that they must take out new loans simply to pay the interest on the old ones … [Regarding] risk from China’s debt pile … [i]f the government continues to insist on organizing the financial system so that a disproportionate share of credit flows to low-return state sector projects, the sustainable growth rate of the economy is likely to decline over time.

A significant reason for China’s recent moves away from free market reforms was the global financial crisis of 2008, which was precipitated by U.S. policies. As Kroeber writes:

[T]he fact that the global crisis originated in the United States undermined the credibility of pro-market reformers in China who took the United States as their model, and strengthened the hand of conservative officials who wanted a permanent strong state role in the economy. This shift toward a more powerful state sector was summarized in a popular phrase of that time: guo jin min tui, or “the state advances and the private sector retreats.”

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore how China implements property rights, its policies on freedom of thought, and prospects for political and economic reform.