Capitalism and Progress – Part 3

How a too limited understanding of history leads to an inaccurate perception of binary “good” or “bad” forces in history.

A limited understanding of history can lead to the false understanding of reality as the result of binary “good” or “bad” historical forces. One example is the false narrative espoused by Ibram X. Kendi and the “1619 Project.” As Thomas Sowell has written in Black Rednecks and White Liberals:

Where the quest for injustice is over-riding, among the things it overrides are logic and evidence. For example, various kinds of differences between white and aboriginal Australians were lumped together by a white Australian woman as examples of social injustice: “The fact that I wake up each morning in a warm, safe, comfortable home, secure in the knowledge that the schools I send my children off to are organised to enhance their life chances and choices, and that good health, employment opportunities and respect are the norm not the goal in our lives has been made possible through the 208-year exploitation of land that belonged to indigenous Australians since the beginning of time.” Here differences in life chances are attributed to the seizure of land by the transplanted Europeans who settled Australia. If this were meant seriously as an empirical proposition, rather than as an ideological indictment, then the most obvious question would be: Were there no differences in life chances between the Europeans and the aborigines before they met, when they were each living in their own respective homelands? Are differences today greater than they were then? None of this provides a moral justification for the invasion of Australia, but it raises a question about the causal claim that differences in life chances today are due to expropriations of land in the past or exploitation of the indigenous people then or now. Had no invasion of Australia ever occurred, and this white Australian woman had been born in the land of her ancestors—probably England—would she not have awakened each morning to better circumstances and prospects than aborigines in a distant and undisturbed Australia? Nor would she have been any more deserving of this windfall gain in England than in Australia. Yet her sense of guilt for her personal advantages and her ancestors’ sins is greater because she lives in Australia. More important, it leads her to a conclusion all too characteristic of the quest for cosmic justice—that the aborigines should not have to change in order to achieve equality of results with whites in Australia. Clearly, the aborigines would have had to change in order to achieve equality of economic results with Englishmen, had both remained alone in their respective homelands. Yet those with the vision of cosmic justice want both groups to have the same effects without having the same causes, when both are living in the same country … Despite vast differences in income and wealth between Europeans and Africans in their respective homelands, much smaller differences between the descendants of Europeans and the descendants of Africans in the United States are widely attributed to the sins of the former against the latter. Had both groups migrated voluntarily to America and both been treated fairly, there would still have been no reason whatever to expect their economic levels to be the same, especially since people who did migrate voluntarily from different parts of Europe had income and wealth differences that were at one time greater than those between black and white Americans today. None of this denies that there were in fact sins committed by whites against blacks in the United States or by the British against the aborigines in Australia. Those sins are not in dispute. The point here is that statistical disparities are not evidence of either the existence or the magnitude of those sins, for which there is ample other evidence. Such disparities are all too common around the world—with and without discrimination, with and without invasion, with and without slavery … In a sense, it is healthy that more prosperous individuals or societies recognize that their prosperity is not all due to what they themselves have done in their own lifetimes, but is in fact the fruit of the efforts and contributions made by many other people before they were born. However, gratitude for whatever has made their prosperity possible has for many been replaced by guilt for having been more fortunate than others. Thus their forebears are seen not as having bequeathed a valuable heritage but as having perpetrated great injustices.

Regarding slavery, David Landes, in his book The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Are Some So Rich and Some So Poor, describes how slavery in Africa grew out of its hot climate and pestilent environment:

In general the discomfort of heat exceeds that of cold. We all know the fable of the sun and wind. One deals with cold by putting on clothing, by building or finding shelter, by making fire. These techniques go back tens of thousands of years and account for the early dispersion of humanity from an African origin to colder climes. Heat is another story. Three quarters of the energy released by working muscle takes the form of heat, which the body, like any machine or engine, must release or eliminate to maintain a proper temperature. Unfortunately, the human animal has few biological devices to this purpose. The most important is perspiration, especially when reinforced by rapid evaporation. Damp, “sweaty” climes reduce the cooling effect of perspiration — unless, that is, one has a servant or slave to work a fan and speed up evaporation. Fanning oneself may help psychologically, but the real cooling effect will be canceled by the heat produced by the motor activity. That is a law of nature: nothing for nothing; or in technical terminology, the law of conservation of energy and mass … The easiest way to reduce this waste problem is not to generate heat; in other words, keep still and don’t work. Hence such social adaptations as the siesta, which is designed to keep people inactive in the heat of midday. In British India, the saying had it, only mad dogs and Englishmen went out in the noonday sun. The natives knew better … Slavery makes other people do the hard work. It is no accident that slave labor has historically been associated with tropical and semitropical climes … Heat, especially year- round heat, has an even more deleterious consequence: it encourages the proliferation of life forms hostile to man. Insects swarm as the temperature rises, and parasites within them mature and breed more rapidly. The result is faster transmission of disease and development of immunities to countermeasures. This rate of reproduction is the critical measure of the danger of epidemic: a rate of 1 means that the disease is stable— one new case for one old. For infectious diseases like mumps or diphtheria, the maximum rate is about 8. For malaria it is 90. Insect- borne diseases in warm climes can be rampageous. 10 Winter, then, in spite of what poets may say about it, is the great friend of humanity: the silent white killer, slayer of insects and parasites, cleanser of pests … Tropical countries, except at higher altitudes, do not know frost; average temperature in the coldest month runs above 18C. As a result they are a hive of biological activity, much of it destructive to human beings. Sub-Saharan Africa threatens all who live or go there … In the case of African trypanosomiasis, the vector is the tsetse fly, a nasty little insect that would dry up and die without frequent sucks of mammal blood. Even today, with powerful drugs available, the density of these insects makes large areas of tropical Africa uninhabitable by cattle and hostile to humans. In the past, before the advent of scientific tropical medicine and pharmacology, the entire economy was distorted by this scourge: animal husbandry and transport were impossible; only goods of high value and low volume could be moved, and then only by human porters. Needless to say, volunteers for this work were not forthcoming. The solution was found in slavery, its own kind of habit- forming plague, exposing much of the continent to unending raids and insecurity. All of these factors discouraged intertribal commerce and communication and made urban life, with its dependence on food from outside, just about unviable. The effect was to slow the exchanges that drive cultural and technological development.

Slavery was also widespread in Africa because tropical temperatures bred insects that targeted animals, inhibiting animal domestication for use in transporting goods and cultivating crops. So human slaves were used instead. As Landes describes in his book The Wealth and Poverty of Nations:

In the case of African trypanosomiasis, the vector is the tsetse fly, a nasty little insect that would dry up and die without frequent sucks of mammal blood. Even today, with powerful drugs available, the density of these insects makes large areas of tropical Africa uninhabitable by cattle and hostile to humans. In the past, before the advent of scientific tropical medicine and pharmacology, the entire economy was distorted by this scourge: animal husbandry and transport were impossible; only goods of high value and low volume could be moved, and then only by human porters. Needless to say, volunteers for this work were not forthcoming. The solution was found in slavery, its own kind of habit-forming plague, exposing much of the continent to unending raids and insecurity. All of these factors discouraged intertribal commerce and communication and made urban life, with its dependence on food from outside, just about unviable. The effect was to slow the exchanges that drive cultural and technological development.

Lewis Gann and Peter Duigan describe African South of the Sahara before and after the Western colonial era in their book Burden of Empire as follows:

African societies also faced a host of major ecological difficulties. Vast areas suffer from irregular rainfall and drought. Even the verdant forest belts, whose vegetation seems so lush, must cope with soil leaching and sometimes with irregular precipitation, which make farming a gamble. African ethics therefore emphasized the virtues of cooperation rather than individual advancement. There were some societies, like those of the Ganda, where there was a considerable degree of social mobility, but by and large, honor went to the good neighbor and power went to the generous lord. To the Bantu, as to the Anglo-Saxon of old, the king was a hláford, a “loaf ward” or bread giver who made gifts to his followers and fed the hungry when the crops failed. In a society with few means of storing food over long periods, generosity was indeed the best policy. The road to power lay through a man's ability to secure the loyalty of his relatives and the allegiance of strangers by judicious gifts. There was also an element of economic compulsion. In many African societies chiefs could enforce short periods of compulsory labor which enabled them to build up a small surplus of food. A powerful ruler moreover collected tribute, but much of this was redistributed in the form of gifts. Niggardliness, on the other hand, was the mark of the bad citizen; the man who took all and gave nothing, whose crops flourished when everyone else's failed, was likely to be killed on charges of practicing witchcraft … The Bantu, unlike the Christian or the Jew, had no “portable motherland,” a rigidly defined system of faith which he might carry to the ends of the earth. Nor could he conceive of individual rights, apart from and independent of the community … But emphasis in general lay on the group, and individualism was discouraged … Tribal cultures had many achievements to their credit, but they also had many defects which no amount of romanticizing or appeal to philosophies of cultural relativism can explain away. The tribal community restricted the over-all development of the community and of individuals. Its outlook and public philosophy were narrow. Essentially the tribe aimed, successfully or not, at preserving the status quo. Fear of witchcraft restricted innovation. The kinship system, for all its admirable qualities, also made people less venturesome and restricted economic development. Other unattractive aspects in many tribal communities included domestic slavery, the frequent practice of infanticide, the execution of suspected witches, ritual murders, and the widespread custom of killing people to accompany the dead king into the nether world. The mutilation or torture of criminals and the slaughter of prisoners were common … Sub-Saharan Africa was never able to solve fully its economic problems; its exports were limited and its natural wealth remained small. There was, however, one commodity which for many centuries found an ever-increasing market. This was muscle power, the working capacity of Africa's own sons and daughters. The disastrous combination of an unsatisfied demand for foreign trade goods with an insatiable demand for slaves in the Americas and in the Muslim world resulted in the development of a traffic in slaves that in time came to dominate much of Africa's economic life. In its earliest form this commerce did not originate in the West. Slave dealing in the Sudan dates back to remotest antiquity; the slave trade was Africa's first form of labor migration. From time immemorial, Egypt, North Africa, and the Middle East purchased black people from the south who did duty as servants and farmhands, as soldiers and palace guards, as eunuchs and concubines … Some historians now largely ascribe Africa's technological and material backwardness to the effects of the slave trade and to the loss of population which the traffic entailed … The evidence is not, however, clear-cut. Barotseland remained relatively sheltered from the incursions of slave traders into the interior of southern Africa. The Lozi ruling class had little interest in exporting much-needed manpower; on the contrary, they preferred to raid their neighbors on their own account. The kingdom was also protected by sheer distance from the main centers of slave dealing in Angola and the East Coast. Nevertheless, Barotseland never attained a higher level of material civilization than the West African states which did participate in slave traffic. Lozi politics also had a dark side, with tortures, liquidations, and other refinements of cruelty that owed nothing to foreign pressure or inspiration.26 Cannibalism—a custom adopted by some African communities either for ritual purposes or for the sake of obtaining a more varied diet—flourished among people like the Ibo of Nigeria, who were involved in the slave trade; cannibalism, however, was also popular with the Zimba, a conquering horde who terrorized various parts of East Africa during the sixteenth century but did not sell their captives to the Christians … The effects of manpower losses brought about by the slave trade are equally difficult to assess. Daniel Neumark, a modern economic historian who has gone over the slave-trade figures, estimates that if the total population of West Africa during the slave-trade period stood at no more than 20 million, the average loss would have amounted to a maximum of 0.5 percent a year. Slave depredations, however, were very unevenly spread. The strong and highly centralized black states of the coastal regions, which managed to monopolize the traffic with the hinterland, prospered amazingly; kingdoms such as Oyo, Dahomey, and Ashanti owed their greatness and prosperity to slave dealing. Thus some areas derived considerable economic benefit from the trade. Oddly enough, it is precisely those parts of West Africa which might be assumed to have suffered most from the slave trade—the Gold Coast and what is now southern Nigeria—that comprise today some of the most advanced and densely populated districts of the country. Even when the slave trade was at its highest, these regions were remarkable for the density of their population and for their elaborate political organization. In some instances the expansion of trade acted as a stimulus to the growth of population by the introduction of American plants and fruit.29 It also contributed to the development of more centralized forms of political rule. The export of slaves enabled Africans to purchase consumer goods which they could not have afforded otherwise. All in all, slave traffic probably gave even more employment to African than to European dealers. No wonder, therefore, that the British abolition of the slave trade in 1807 led to bitter African discontent on the Gold Coast … The damage inflicted on parts of Africa was nevertheless disastrous. Outlying regions on the periphery of the slave-trading states suffered with special severity; so did the less densely populated regions, which could not easily stand any additional loss of manpower. Slave trading represented not merely an inhuman system, but also a serious diversion of economic resources. Imported guns made warfare more destructive in its effects; the trade in firearms certainly gave an added advantage to freebooting chiefs, able to acquire the discarded weapons of the West for use against less well equipped neighbors and rivals. Slave-trading kingdoms themselves became demoralized. Human sacrifice flourished in Benin; Dahomey at the end of the century presented a picture not of youthful vigor, but of bloodstained decadence.

The demand for slaves in Muslim territories in the Middle East was so great it was the major source of profits in trading between Europe and the Middle East throughout the Early and High Middle Ages, only to be taken over by a trade dominated by Muslim African slave ports during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. This commerce in slaves to the Middle East is described by Michael McCormick in his book Origins of the European Economy. As described in Paul E. Lovejoy’s book Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa (Third Edition), between 1400 and into the Twentieth Century, interpretations of Islam that justified the enslavement of infidels produced the large majority of slaves in Africa, which were the source of slaves for the transatlantic slave trade to America and the Middle East. These Islamic warlords and regimes also enslaved white Christians in huge numbers. According to Robert C. Davis in his book Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast, and Italy, 1500-1800:

[B]etween 1530 and 1780 there were almost certainly a million and quite possibly as many as a million and a quarter white, European Christians enslaved by the Muslims of the Barbary Coast … In fact, even a tentative slave count in Barbary inevitably begs a host of new questions. To begin with, the estimates arrived at here make it clear that for most of the first two centuries of the modern era, nearly as many Europeans were taken forcibly to Barbary and worked or sold as slaves as were West Africans hauled off to labor on plantations in the Americas.

When the Muslim Ottoman provinces of Northern Africa authorized ships to capture and enslave Americans at sea, President Jefferson sent the Marines to stop them.

As described by historian James Walvin in his book A Short History of Slavery, “The Islamic tradition of enslavement … meant that, in the very years when slavery was in sharp decline elsewhere in Europe, slavery was confirmed as an unquestioned feature of Iberian life,” which ultimately made its way to the Caribbean and South America through the discoveries of Christopher Columbus on behalf of Spain. Walvin continues, “Though the enslavement of fellow Muslims was disapproved of, in time this came to be overlooked or ignored by Muslim slave traders … In time, it came to be assumed that black Africans were natural slaves, through this had not been the case initially ... Arabs/Muslims began to think of black Africans as ideally suited for slavery. Gradually, a distinct racial prejudice emerged.” As James Sweet has chronicled in “The Iberian Roots of American Racist Thought,” the racism that came to characterize American slavery derives in part from the cultural and religious history of Islam, as Islamic attitudes about blacks and slavery spread to Spain, Europe generally, and then America. He writes “By the fifteenth century, many Iberian Christians had internalized the racist attitudes of the Muslims and were applying them to the increasing flow of African slaves to their part of the world ... Iberian racism was a necessary precondition for the system of human bondage that would develop in the Americas during the sixteenth century and beyond.” As Bernard Lewis has further described in his book Race and Slavery in the Middle East, “Inevitably, the large-scale importation of African slaves influenced Arab (and therefore Muslim) attitudes to the peoples of darker skin whom most Arabs and Muslims encountered only in this way.” As historian David Brion Davis explains in his book Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World, “The Arabs and other Muslim converts were the first people to make use of literally millions of blacks from sub-Saharan Africa and to begin associating black Africans with the lowliest forms of bondage … racial stereotypes were transmitted, along with black slavery itself … as Christians treated and fought with Muslims for the first Islamic challenges to the Byzantine Empire, in the seventh and eighth centuries, through the era of the crusades.” Slavery also continued, and continues, long after it was abolished in the Americas. As James Walvin writes, “By 1888, slavery had been swept away across the Americas. The same could not be said for Africa, however. Indeed, at the very point when Americans shed their appetite for black slaves, there may have been more slaves in Africa than ever before, more even than had been shipped across the Atlantic in the entire history of Atlantic slavery.” Henry Louis Gates Jr., the chair of Harvard’s Department of African and African American Studies, has rebuked the founder of the “1619 Project” for the decision to ignore the role played by African warlords, who kidnapped blacks for the slave trade. “Talk about the African world and the slave trade,” Gates urged her. “This is something black people don't want to talk about. ... This has got to be full disclosure. And we’ve got to talk about that.”

Basil Davidson, in his book The African Slave Trade, explains how African rulers voluntarily negotiated their own monopoly on slave sales and delivery on the African coast that benefited them financially, and how the slave trade generally hurt the economic and technological development of Africa, and how the detrimental effects of these many centuries of slave trade swamped any negative effects of colonialization (which lasted only a few generations).

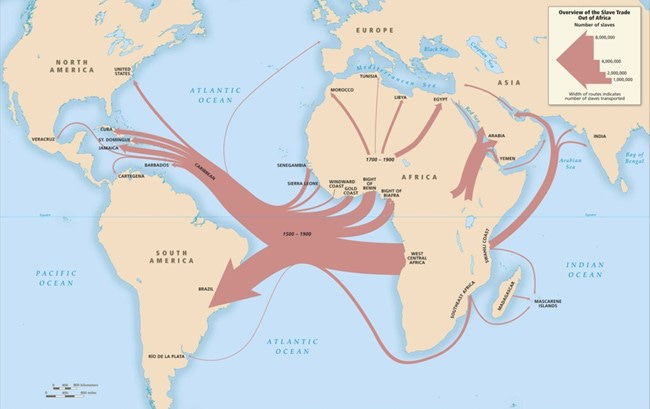

This map shows the volume of slaves sold by African slave traders worldwide.

Slavery was so widespread in Africa that Benjamin Franklin wrote a parody, published in the Federal Gazette on March 23, 1790, comparing Southern slaveholders' arguments against the abolition of slavery to the arguments that might be used by a Muslim pirate slaver if there were to be a similar abolitionist movement in Africa:

Allah Bismillah, &c. God is great, and Mahomet is his Prophet.

Have these Erika considered the Consequences of granting their Petition? If we cease our Cruises against the Christians, how shall we be furnished with the Commodities their Countries produce, and which are so necessary for us? If we forbear to make Slaves of their People, who in this hot Climate are to cultivate our Lands? Who are to perform the common Labours of our City, and in our Families? Must we not then be our own Slaves? And is there not more Compassion and more Favour due to us as Mussulmen, than to these Christian Dogs? We have now about 50,000 Slaves in and near Algiers. This Number, if not kept up by fresh Supplies, will soon diminish, and be gradually annihilated. If we then cease taking and plundering the Infidel Ships, and making Slaves of the Seamen and Passengers, our Lands will become of no Value for want of Cultivation; the Rents of Houses in the City will sink one half; and the Revenues of Government arising from its Share of Prizes be totally destroy’d! And for what? To gratify the whims of a whimsical Sect, who would have us, not only forbear making more Slaves, but even to manumit those we have.

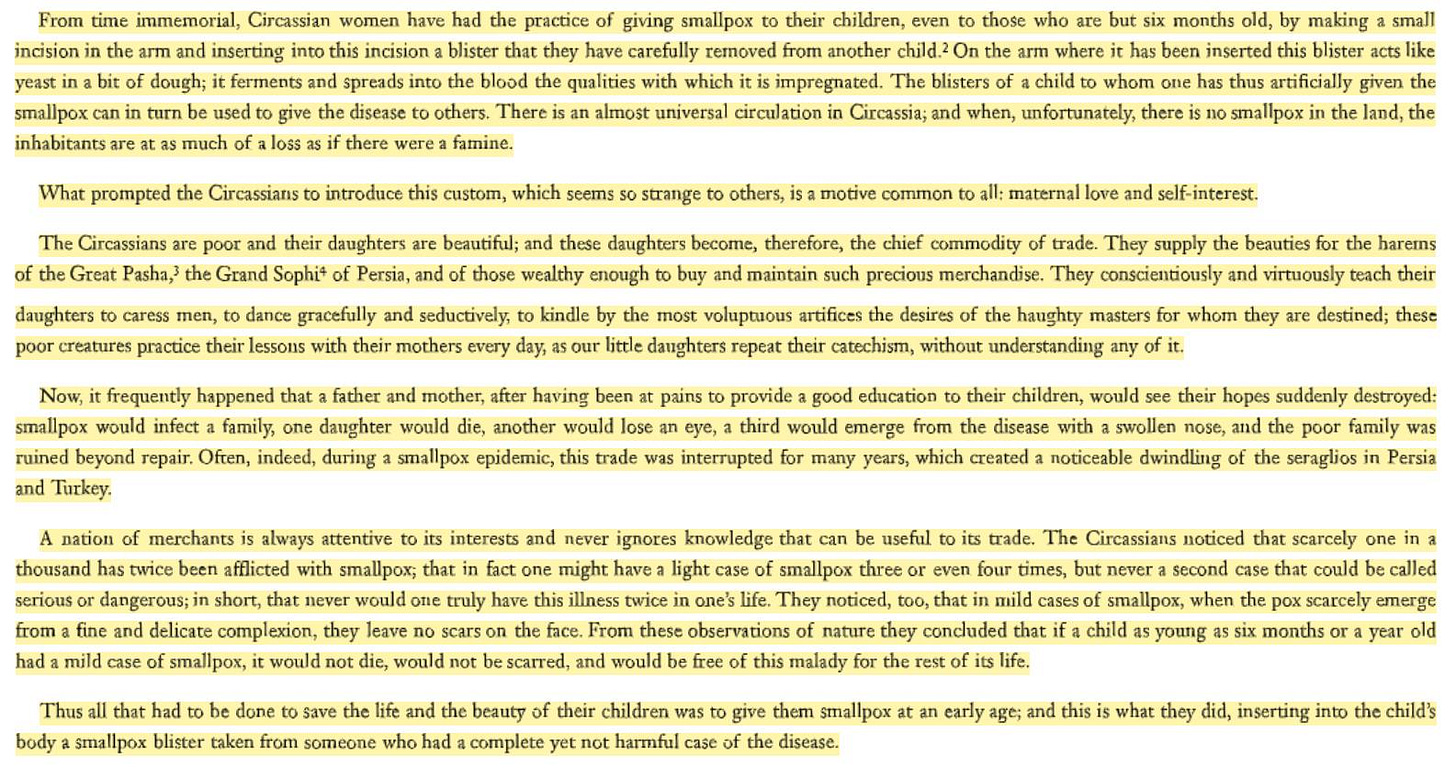

The Ottoman Empire’s lucrative markets in female slaves even spurred the practice of inoculation (early vaccines) against smallpox, which originated to prevent girls from suffering the facial scarring resulting from surviving smallpox, scars that would have made them less marketable as sexual slaves. As Voltaire describes in his Eleventh Letter of his “Philosophical Letter, or Letters Regarding the English Nation” (referring to Circassians, a Northwest Caucasian group north of Turkey that was attacked and raided by Ottoman Tartan tribes to the south):

The Founding Fathers generally opposed slavery as a national policy. As Thomas Sowell has pointed out:

Slavery was just not an issue, not even among intellectuals, much less among political leaders, until the 18th century – and then it was an issue only in Western civilization. Among those who turned against slavery in the 18th century were George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry and other American leaders. You could research all of the 18th century Africa or Asia or the Middle East without finding any comparable rejection of slavery there. But who is singled out for scathing criticism today? American leaders of the 18th century.

As Kevin Kallmes points out:

Even given his personal slaves, Jefferson made his moral stance on slavery quite clear through his famous efforts toward ending the transatlantic slave trade, which exemplify early steps in securing the abolition of the repugnant act of chattel slavery in America and applying classically liberal principles toward all humans. However, this very practice may have been enacted far sooner, avoiding decades of appalling misery and its long-reaching effects, if his (hypocritical but principled) position had been adopted from the day of the USA’s first taste of political freedom. This is the text of the deleted Declaration of Independence clause: “He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the Christian King of Great Britain. Determined to keep open a market where Men should be bought and sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or restrain this execrable commerce. And that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, by murdering the people on whom he has obtruded them: thus paying off former crimes committed against the Liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another …” The second Continental Congress, based on hardline votes of South Carolina and the desire to avoid alienating potential sympathizers in England, slaveholding patriots, and the harbor cities of the North that were complicit in the slave trade, dropped this vital statement of principle. The removal of the anti-slavery clause of the declaration was not the only time Jefferson’s efforts might have led to the premature end of the “peculiar institution.” Economist and cultural historian Thomas Sowell notes that Jefferson’s 1784 anti-slavery bill, which had the votes to pass but did not because of a single ill legislator’s absence from the floor, would have ended the expansion of slavery to any newly admitted states to the Union years before the Constitution’s infamous three-fifths compromise. One wonders if America would have seen a secessionist movement or Civil War, and how the economies of states from Alabama and Florida to Texas would have developed without slave labor, which in some states and counties constituted the majority. These ideas form a core moral principle for most Americans today, but they are not hypothetical or irrelevant to modern debates about liberty. Though America and the broader Western World have brought the slavery debate to an end, the larger world has not; though countries have officially made enslavement a crime (true only since 2007), many within the highest levels of government aid and abet the practice. 30 million individuals around the world suffer under the same types of chattel slavery seen millennia ago, including in nominal US allies in the Middle East.

Sean Wilenz, in his book No Property in Man, describes how the Founders specifically denied a federal right to “property in man” when drafting the Constitution, and how abolitionists used the federal power to prohibit slavery in new territories and states led to Abraham Lincoln’s election and, as a result, the secession of Southern states, and the Union’s ultimate victory in the Civil War.

Slavery in America wasn’t a capitalist or free market regime in any way. As explained by Allen Guelzo:

The clinching refutation of the slavery-is-capitalism theory comes from the mouths of the slave owners themselves. They would have been aghast at the idea they were presiding over Yankee capitalism. Capitalism, complained slavery’s paladin, John C. Calhoun, “operated as one among the efficient causes of that great inequality of property which prevails in most European countries. No system can be more efficient to rear up a moneyed aristocracy. Its tendency is, to make the poor poorer, and the rich richer.” The 1619 Project imagines Southern slaveholders were practicing “capitalism” simply because they made money. But slavery had been around since antiquity—long before anything resembling capitalism existed. And what the South saw in its plantations wasn’t capitalism but the opposite. Writing in 1854, the pro-slavery propagandist George Fitzhugh described slavery as “a beautiful example of communism, where each one receives not according to his labor, but according to his wants.”

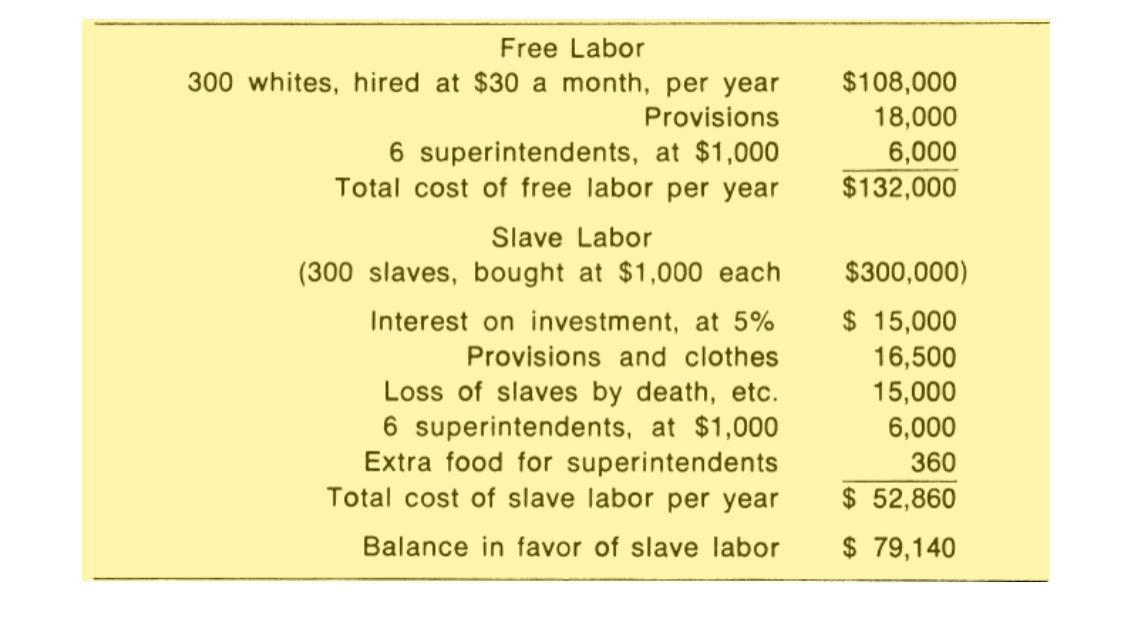

Also, a reliance on human slavery made the American South poorer than the North, and less industrialized, making the South less able to produce the sorts of things necessary to win wars, including the Civil War. As explained Benjamin Arrington, “As both the North and the South mobilized for war, the relative strengths and weaknesses of the ‘free market’ and the ‘slave labor’ economic systems became increasingly clear - particularly in their ability to support and sustain a war economy. The Union's industrial and economic capacity soared during the war as the North continued its rapid industrialization to suppress the rebellion. In the South, a smaller industrial base, fewer rail lines, and an agricultural economy based upon slave labor made mobilization of resources more difficult. As the war dragged on, the Union's advantages in factories, railroads, and manpower put the Confederacy at a great disadvantage.” Indeed, as pointed out by historian Timothy Winegard, Abraham Lincoln recognized that slavery made everyone poorer: “While Lincoln repeatedly assured the slave states that he would not abolish the institution where it already existed, he was also adamant that slavery could not spread west into new states and territories. Poor white farmers, like his own father, needed an opportunity to make a decent living farming food crops on ‘free soil’ detached from the no-win wage competition with unpaid slave labor. The simple economics of slavery impoverished all spectrums of American society, slaves and freemen alike.”

Slavery also greatly reduced the wages of Southern white laborers, who had to work for less than the cost of slave labor to get jobs, as described in William Julius Wilson’s The Declining Significance of Race. A table illustrating this dynamic is below.

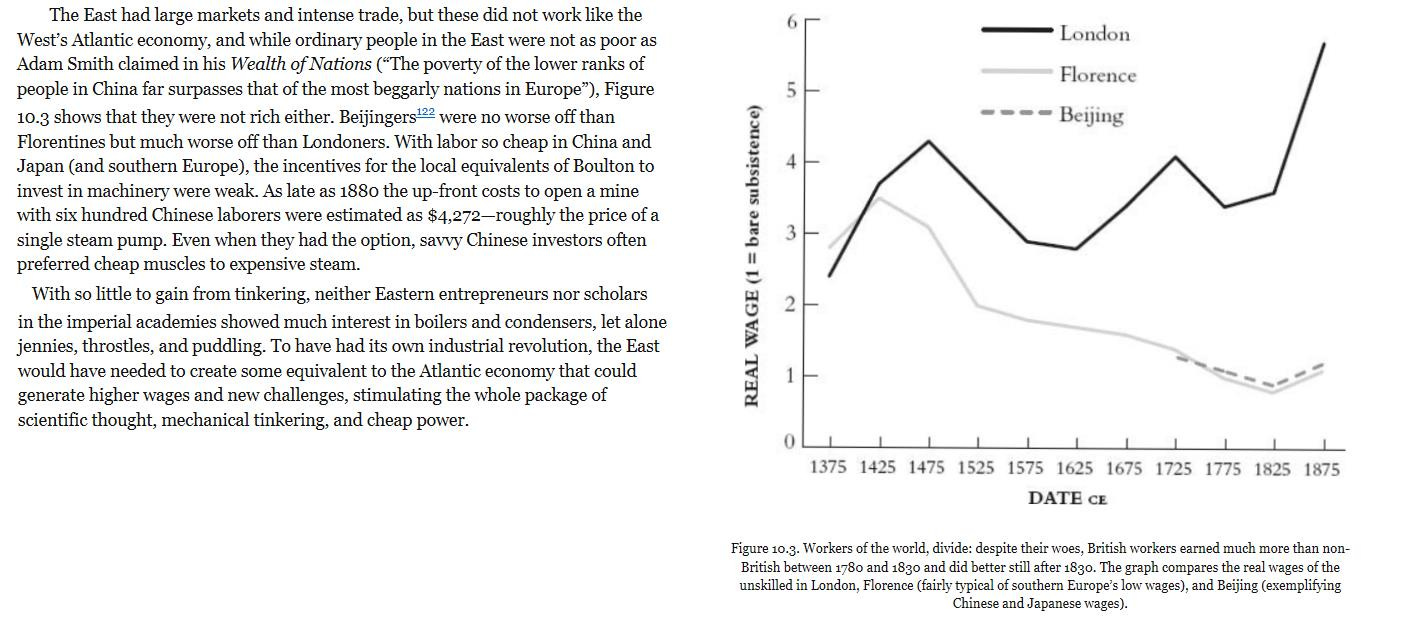

(Incidentally, historian Ian Morris, in his book “Why the West Rules – For Now,” also points out that for the same reasons, China fell behind England starting in the 1400’s, as China’s reliance on cheap forced labor to perform tasks denied it the incentives necessary to spur the scientific thought and mechanical tinkering that was used during the Industrial Revolution to produce cheaper power.)

The South’s reliance on slave labor over work done by technology and machines significantly reduced its prosperity and productivity. As Thomas Sowell describes in his book Wealth, Poverty, and Politics:

The prevalence of such attitudes is another cultural handicap for any group or nation, especially those currently lagging economically. Sometimes the problem is not just an aversion to work, or to certain kinds of work, but also a lack of drive for progress. Here again, America’s antebellum South was an example: Techniques of Southern agriculture changed slowly, or not at all. So elementary a machine as the plow was adopted only gradually and only in scattered places; as late as 1856, many small farmers in South Carolina were still using the crude colonial hoe. There was little change in the cotton gin, gin house, or baling screw between 1820 and the Civil War. The cotton gin, a crucial factor in the economy of the antebellum South, was invented by a Northerner. When it came to inventions in general, only 8 percent of the U.S. patents issued in 1851 went to residents of the Southern states, whose white population was approximately one-third of the white population of the country. Even in agriculture, the main economic activity of the region, only 9 out of 62 patents for agricultural implements went to Southerners. The lesser dedication of Southerners to economic activity, and a corresponding lesser investment in their own human capital, was also reflected in lower levels of skills in the South, both among labor and management.

Claims that slaves made cotton the dominant product in the American economy, and that high slave productivity was driven by increasingly harsh punishments, have been widely debunked by economic historians, as explained by Alan Olmstead’s and Paul Rhodes in their article “Cotton, Slavery, and the New History of Capitalism.”

Robert William Fogel, a Nobel Prize winner in economics, co-wrote a book, Time on the Cross, showing how slavery largely denied the South the benefits of industrialization. Robert William Fogel further explores how slavery slowed Southern industrialization, and the route to success of the abolitionist movement, in his book Without Consent or Contract.

Economic historians have shown that, due to intense competition, African slave sales were not profitable for anyone involved in the trade — except perhaps the Africans who captured them, but even then the chaos that surrounded a universal fear of slave-taking by neighboring African tribes dramatically reduced the well-being of Africans overall. Like the Aztecs, who submitted their victims to human sacrifice instead of membership in a wider tax-paying citizenry, African warlords depleted their own human resources in return for meager, if any, profits. Robert Paul Thomas and Richard Nelson Bean explore these issues in “The Fishers of Men: The Profits of the Slave Trade.”

The greater economic prosperity enjoyed by the non-slave North led to larger increases in population than in the less economically-developed South, a population advantage that also gave the North an edge during the Civil War. As Sean Wilenz writes in No Property in Man, “The bonus given by the three-fifths clause, which southerners had supposed would secure them a majority in the House and the Electoral College, had long since failed to keep pace with a relative rise in northern population, and the disparity kept getting worse. In 1820, the non-slaveholding states (including those that had commenced emancipation) held 123 seats in the House, compared to 90 held by the slave states; in 1850, the respective figures were 147 and 90. In 1856, the Electoral College favored the non-slave states by a margin of 176 to 120.”

Both free and enslaved blacks used resourceful techniques to conduct their own businesses around the barriers they faced, just as resourceful entrepreneurs today have sought to circumvent lesser restrictions on their business activities imposed by government. John Butler explores these issues in his book Entrepreneurship and Self-Help Among Black Americans: A Reconsideration of Race and Economics, Revised Edition.

Researcher Zora Neale Hurston interviewed Cudjo Lewis, one of the last African slaves brought to America (illegally) in 1860. Cudjo Lewis’s own description of his enslavement in Africa by a competing black African tribe is recounted in Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” written in 1927. The book could not find a publisher at the time in part because it contradicted the popular myth that black slaves from Africa were lured into capture by white slave traders, when in fact they were enslaved by other black tribes, and only then sold to white buyers. As Ms. Hurston writes, “One thing impressed me strongly from this three months of association with Cudjo Lewis. The white people had held my people in slavery in America. They had bought us, it is true and exploited us. But the inescapable fact that stuck in my craw, was: my people had sold me and the white people had bought me. That did away with the folklore I had been brought up on—that the white people had gone to Africa, waved a red handkerchief at the Africans and lured them aboard ship and sailed away.”

Essays in the book Red, White, and Black make the following additional points rebutting the false narrative presented by the 1619 Project:

[Frederick] Douglass noted, “I know of no rights of race superior to the rights of humanity.” A steadfast believer in equality under the law, he insisted that the “Constitution knows no man by the color of his skin” and therefore did not believe race should be the measure of anyone’s constitutional rights. In this focus upon his rights as an American citizen and not as a black man, Douglass foreshadowed Justice Louis Harlan’s famous, lone dissenting opinion in the infamous 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case, which produced the insidious doctrine of “separate but equal.” Harlan wrote, “Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.” … In [Frederick] Douglass’s words, “color should not be a criterion of rights.”

In ten years of the Depression, when the United States overall had a negative GNP and a nearly 25 percent unemployment rate, the unemployment rate in the black community was over 40 percent. Even then, the marriage rate in the black community was higher than it was in the white community, despite times of economic deprivation and racism. In 1925 in New York City, 85 percent of black families were a husband and wife raising their children—while today the rate of out-of-wedlock births among blacks has skyrocketed to nearly 71 percent.

[T]he gap between white and black Americans in terms of the likelihood of being shot by the police—blacks make up 13 percent of the country and 25 to 30 percent of shooting victims in a typical year—vanishes if an adjustment is made for the black crime rate, generally 2.1 to 2.4 times the white rate. Further evidence for the non-nightmarish nature of contemporary America comes from the success of many recent minority immigrant groups. A 2014 Census Bureau graphic—so pleasantly surprising to many middle-class people of color that it became a trending online meme—noted that the highest-income racial/ethnic population in the United States is not WASPs, but rather Indian Americans, with a median household income of $100,295. All told, eighteen groups finished ahead of whites, taken en bloc, including Taiwanese Americans ($85,500), Filipino Americans ($82,389), Lebanese Arabs ($69,586), and Nigerians ($61,289). … There is no reason to believe that white racists fancy Yemini Jews or Yoruba tribesmen from Nigeria any more than black Americans, and the visible success of such groups illustrates that racism has declined dramatically—or, at the very least, that performance can dramatically overcome it.

An especially awful effect of that fracturing is the almost universal neglect of poor whites, often dismissed as “deplorables,” by the American taste-making class. Poor white Americans, almost by definition ineligible for both affirmative action and legacy programs, may be the most genuinely neglected population in the modern United States—making up the plurality or majority of those felled annually by suicide, auto wreck, and opiate and other drug overdoses.

All told, about one-tenth of the American men who were of military age in 1860 died as a direct result of the Civil War. Among specifically Southern white men in their early twenties, 22.6 percent—nearly one in four—died during the war. It seems no exaggeration to estimate that roughly one Union soldier died for every nine to ten slaves freed. If the U.S. owed a bill for slavery, we have, quite arguably, already paid it in blood.

Even under slavery, [Walter] Williams points out, “in up to three-quarters of the families, all children had the same mother and father.” In contrast, the black illegitimacy rate today is 75 percent. It seems essentially impossible to attribute this to bigotry, given much less disturbing figures from past historical eras when racism was far worse. And illegitimacy does not stand alone as an outlier: African American rates of incarceration, drug use, STD infection, and unemployment all have been far worse throughout most of the modern era than they were in 1950 …

In sum, the 1619 Project is correct that slavery is an existential horror. However, this practice was not some unique moral failure on the part of the United States. Slavery was the norm everywhere in the world until Western societies began to fight to end it, and the large majority of America’s slaves were purchased from powerful West African and Arab slave traders “of color.” Further, historical slavery did not shape most of the modern institutions of American society. The American region reliant on slave labor was by far the poorest in the country, and almost seven hundred thousand lives were lost when we conquered it and freed the slaves.

Moreover, when I look at the household income of blacks, I also see that reparations have been paid. Yes, the mean black household income of $59,000 is significantly less than that of whites ($89,000), but compare that to the per capita income of the three African countries in my DNA: Cameroon, $1,451; Mali, $827; and Togo, $610.

I am reminded of a student of mine who was wearing a T-shirt depicting a black person in chains with the words “I was not asked to be brought here.” I asked her, “Aren’t you glad you were?” Her answer was, “Oh, my goodness, yes!”

Instead of teaching black children lessons they can use to improve their lives—such as the importance of education and geographic mobility—the 1619 Project seems hell-bent on teaching them to see slavery everywhere: in traffic jams, in sugary foods, and, most surprisingly, in Excel spreadsheets. As Desmond puts it, “When a mid-level manager spends an afternoon filling in rows and columns on an Excel spreadsheet, they are repeating business procedures whose roots twist back to slave-labor camps.”

Jake Silverstein of the Times has written that the arrival of enslaved Africans “inaugurated a barbaric system of chattel slavery that would last for the next 250 years.” Conspicuously absent from the dominant historical narrative is the fact that free blacks and Indian tribes were right there alongside whites, buying and selling slaves after slavery became legal in 1661.

Those who push white guilt and black victimhood ignore critical facts. One is that today’s white Americans are not responsible for the sins of generations ago. Second, slavery was an institution that blacks, Native Americans, and whites participated in as slaveholders. There’s plenty of guilt to go around there.

“There is another class of colored people who make a business of keeping the troubles, the wrongs and the hardships of the Negro race before the public. Having learned that they are able to make a living out of their troubles, they have grown into the settled habit of advertising their wrongs—partly because they want sympathy and partly because it pays. Some of these people do not want the Negro to lose his grievances, because they do not want to lose their jobs.” —Booker T. Washington, My Larger Education, 1911

In his prophetic 1859 “Self-Made Men” speech, Frederick Douglass laid out the path forward based on what he learned from largely unknown, heroic African American figures who triumphed over the most despicable conditions: The lesson taught at this point by human experience is simply this, that the man who will get up will be helped up; and the man who will not get up will be allowed to stay down. This rule may appear somewhat harsh, but in its general application and operation, it is wise, just and beneficent. I know of no other rule which can be substituted for it without bringing social chaos. Personal independence is a virtue and it is the soul out of which comes the sturdiest manhood. But there can be no independence without a large share of self-dependence, and this virtue cannot be bestowed. It must be developed from within.

Insofar as American businesses have adopted Ibram X. Kendi’s and the 1619 Project’s misunderstandings about the world, they have tended to lose support among the American people. As the Wall Street Journal reports:

Big business has helped Americans weather the pandemic. Retailers stayed open, tech firms made remote work possible, and the pharmaceutical industry is cranking out vaccines. So why did satisfaction with the “size and influence of major corporations” fall 15 points in this year's annual Gallup poll to a mere 26%? The collapse came not among Democrats, whose skeptical views were virtually unchanged, but among Republicans. In 2020, 57% of Republicans said they were satisfied with big business. This year the number plummeted to 31%. The likely reason, as NBC’s Alex Seitz-Wald points out, is “the culture war reaching the C-suite.” Put differently, many Fortune 500 firms took the Black Lives Matter protests as an opportunity to pivot hard to the left, ostentatiously endorsing protests even as they sometimes turned violent. Companies from Amazon to Nike donated large sums to progressive activist groups. Managers started to assign polarizing left-wing political texts to employees and adopted new racial hiring preferences.

That concludes this essay series on capitalism and progress. Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays! We’ll be on vacation until December 26.

Paul, Wow...long but fascinating. You may not post again before Christmas, so I thought to wish you and yours a wonderful Christmas and even more deep thoughts in 2025. You have helped make 2024 a brain-expanding year for me and I most appreciate it. Many thanks.