Capitalism and Progress – Part 1

Views on capitalism, and its history.

In this series of essays, we’ll explore what people think of capitalism today, and how puzzling it is there isn’t more support for it, given its results since the Industrial Revolution.

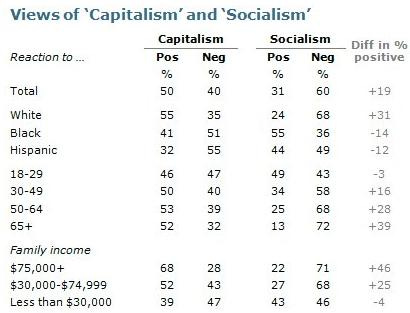

Some of the same demographic groups that elected President Obama had more negative reactions to capitalism and more positive reactions to socialism.

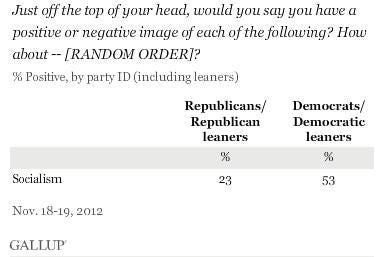

These tendencies are reflected more generally in party affiliation. A majority of Democrats have positive views of socialism.

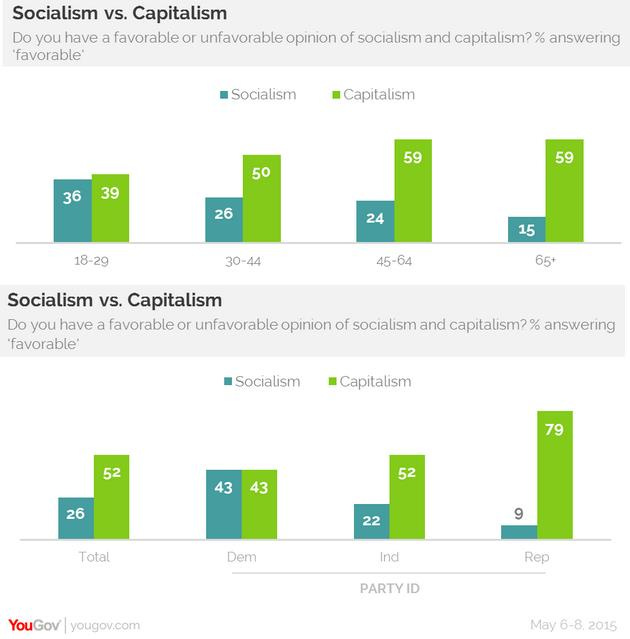

A 2015 poll showed similar results.

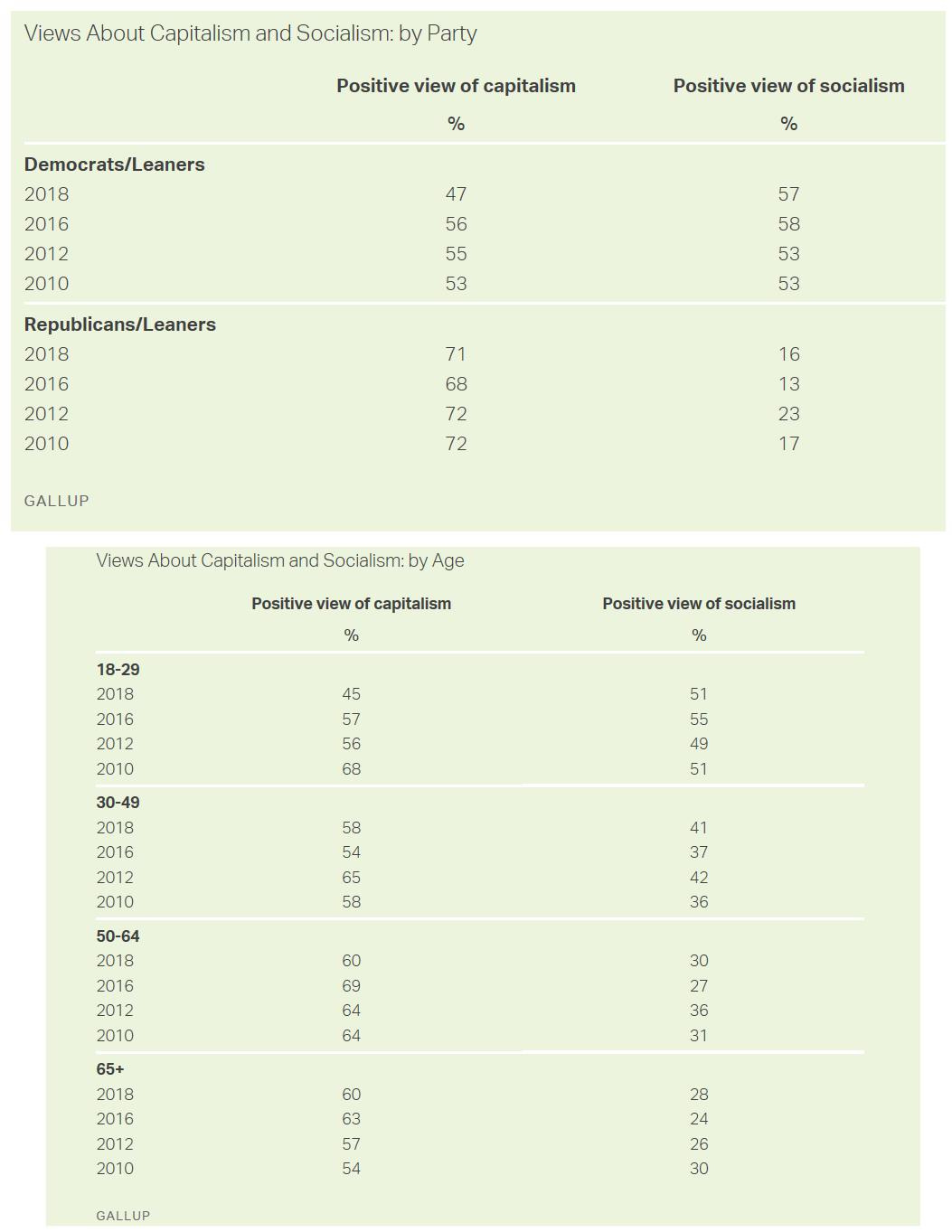

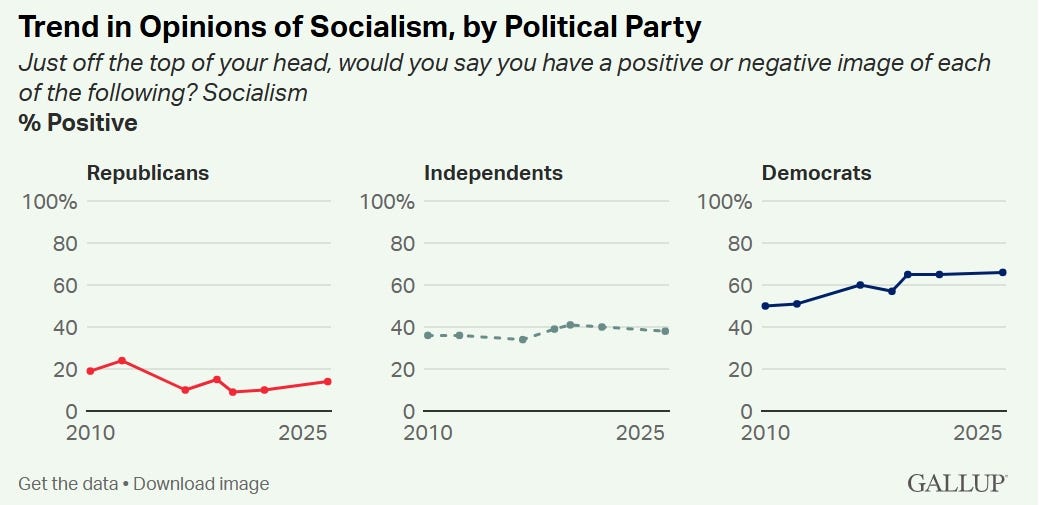

In 2018, for the first time in Gallup’s measurement over the previous decade, Democrats had a more positive image of socialism than they did of capitalism.

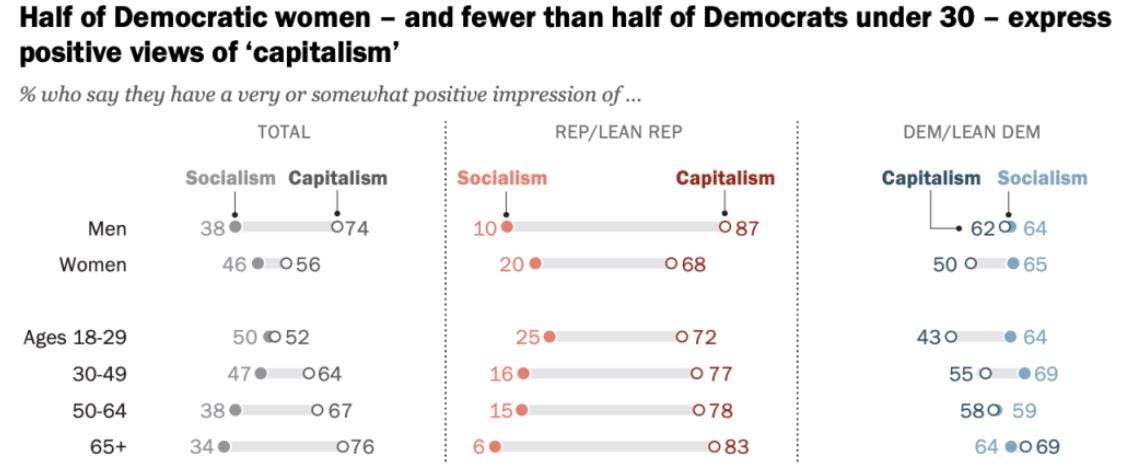

A June, 2019, Pew survey found that Democrats overwhelmingly have more positive views of socialism.

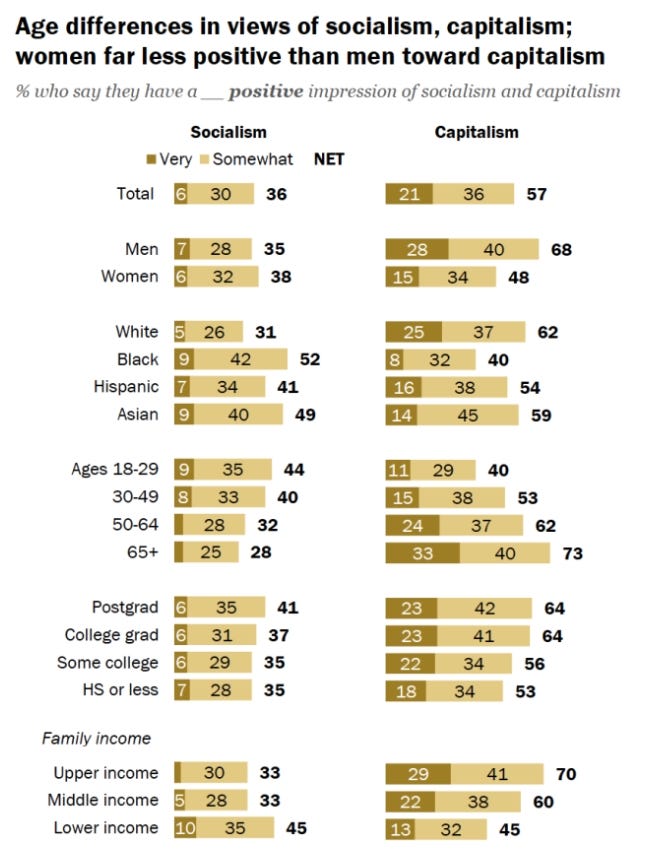

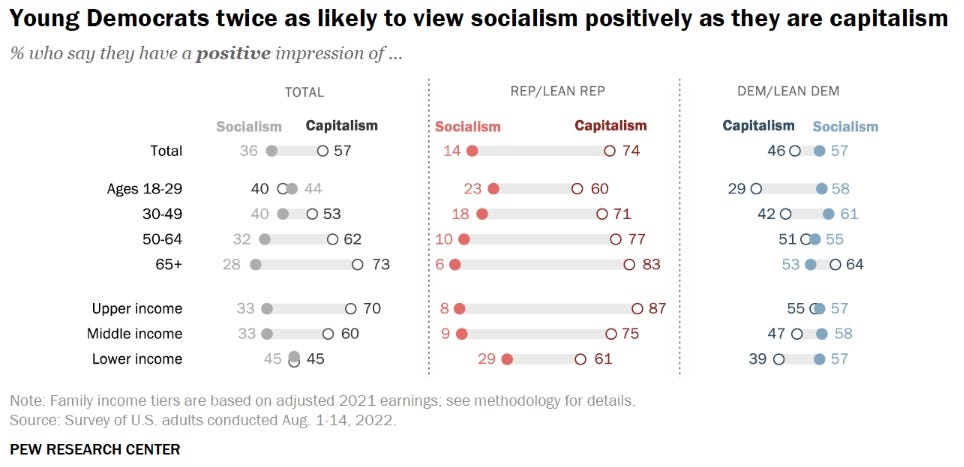

And by 2022, Pew reported that “The American public continues to express more positive opinions of capitalism than socialism, although the shares viewing each of the terms positively have declined modestly since 2019,” with women’s views of capitalism being far less positive, and young Democrats’ being twice as likely to view socialism positively as they are capitalism.

The Gallup poll released in 2025 showed that even more self-identified Democrats have come to support socialism over capitalism:

Democrats are the only partisan group of the three that views socialism more positively than capitalism — 66% to 42%, respectively. Independents are modestly more pro-capitalism than pro-socialism (51% vs. 38%), while Republicans are overwhelmingly so (74% vs. 14%).

These results are odd, given the role capitalism has played in dramatically improving the well-being of people around the world.

The “Washington Consensus” refers to a set of free-market economic policies supported by prominent financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the U.S. Treasury. These policies include:

1. Fiscal policy discipline, with avoidance of large fiscal deficits relative to GDP;

2. Redirection of public spending from subsidies ("especially indiscriminate subsidies") toward broad-based provision of key pro-growth, pro-poor services like primary education, primary health care and infrastructure investment;

3. Tax reform, broadening the tax base and adopting moderate marginal tax rates;

4. Interest rates that are market determined and positive (but moderate) in real terms;

5. Competitive exchange rates;

6. Trade liberalization: liberalization of imports, with particular emphasis on elimination of quantitative restrictions (licensing, etc.); any trade protection to be provided by low and relatively uniform tariffs;

7. Liberalization of inward foreign direct investment;

8. Privatization of state enterprises;

9. Deregulation: abolition of regulations that impede market entry or restrict competition, except for those justified on safety, environmental and consumer protection grounds, and prudential oversight of financial institutions;

10. Legal security for property rights.

Researchers have found that:

Traditional policy reforms of the type embodied in the Washington Consensus have been out of academic fashion for decades. However, we are not aware of a paper that convincingly rejects the efficacy of these reforms. In this paper, we define generalized reform as a discrete, sustained jump in an index of economic freedom, whose components map well onto the points of the old consensus. We identify 49 cases of generalized reform in our dataset that spans 141 countries from 1970 to 2015. The average treatment effect associated with these reforms is positive, sizeable, and significant over 5- and 10- year windows.

Western civilization’s rise from the Middle Ages began with the plague called the Black Death. In The Black Death and the Transformation of the West, David Herlihy and Samuel K. Cohn Jr. describe how the Black Death of the fourteenth century in Europe led to the transformation of the feudal caste system (which itself derived from the Roman Empire’s granting rich Roman landlords the legal right to collect taxes and impose punishments on those who rented land on their estates in the Early Middle Ages) into a freer, more market-driven system:

The civilization that this economy supported, the civilization of the central Middle Ages, might have maintained itself for the indefinite future. That did not happen; an exogenous factor, the Black Death, broke the Malthusian deadlock. And in doing so it gave to Europeans the chance to rebuild their society along much different lines … The legal systems of late medieval Europe also had to respond to the extraordinary social situation created by an epidemic. Under conditions of plague, certain “privileges,” as they were known in the legal language, went into effect.7 Women, for example, could now serve as witnesses, and scribes not formally admitted into the guild of notaries could draw up legal contracts. Society needed certain services, and at these moments of crisis it had to allow even the unlicensed or people believed to be incompetent to perform them … But to enlist constant numbers out of a shrinking pool, the guild had to spread its net broadly and bring in new apprentices with no previous family connection with the trade … Probably in all occupations, the immediate post-plague period was an age of new men … But, over the long run, the breaking of the Malthusian deadlock conferred advantages too. Above all it freed resources. The collapse of population liberated land for uses other than the cultivation of grains. It could be turned to pasturage or to forests. In the past mills and mill sites had served predominantly for the grinding of grain. They now could be enlisted for other uses: the fulling of cloth, the operation of bellows, the sawing of wood. Even as the population shrank, the possibility of developing a more diversified economy was enhanced … Europeans, even as their numbers declined, were living better. Many moralists complain of the extravagant tastes for food and attire which the lower social orders now manifested. Matteo Villani remarks: “The common people, by reason of the abundance and superfluity that they found, would no longer work at their accustomed trades; they wanted the dearest and most delicate foods … while children and common women clad themselves in all the fair and costly garments of the illustrious who had died.” Conspicuous consumption by the humble threatened to erase the visible marks of social distinctions and to undermine the social order. The response of the alleged prodigality in food and clothing was sumptuary laws, which governments enacted all over Europe in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. They tried to regulate fashions, such as the size of sleeves or the length of trains in women’s dresses; meals, such as the food to be served at weddings; or customs, such as the number of mourners who could attend a funeral. The repetition of these laws suggests their futility. High wages to the poor and improved living standards came to be irremediable facts of late medieval economic and social life … Governments tried to cap the swell in wages and to shore up the shrinking rents. They sought to hold prices and wages to previous levels and insisted that workers accept any employment offered them. But they succeeded only in sowing discontent and in provoking social uprisings in city and countryside … Besides commodity prices, the costs of the classical “factors of production”—labor, land, and capital—also responded to the new conditions. Of these production costs, the one most dramatically affected was that of labor. The falling numbers of renters and workers increased the strength of their negotiating position in bargaining with landlords and entrepreneurs. Agricultural rents collapsed after the Black Death, and wages in the towns soared, to two and even three times the levels they had held in the crowded thirteenth century … In the urban economy, the substitution of capital for labor meant the purchase of better tools or machines—devices that enabled the artisan to work more efficiently. Frequently too, the policy of factor substitution involved technological innovation, the development of entirely new tools and machines. High labor costs promised big rewards to the inventors of labor-saving devices. Chiefly for this reason, the late Middle Ages were a period of impressive technological achievement … But the late medieval population plunge raised labor costs, and also raised the premium to be claimed by the one who could devise a cheaper way of reproducing books. Johann Gutenberg’s invention of printing on the basis of movable metal type in 1453 was only the culmination of many experiments carried on across the previous century. His genius was in finding a way to combine several technologies into the new art … The advent of printing is thus a salient example of the policy of factor substitution which was transforming the late medieval economy … Even firearms, another innovative technology of the age, can be interpreted in these terms. Soldiers too were commanding higher wages in depopulated Europe, and soldiers with firearms could fight more effectively than those without. A more diversified economy, a more intensive use of capital, a more powerful technology, and a higher standard of living for the people—these seem the salient characteristics of the late medieval economy, after it recovered from the plague’s initial shock and learned to cope with the problems raised by diminished numbers. Specific changes in technology are of course primarily attributable to the inventive genius of individuals. But the huge losses caused by plague and the high cost of labor were the challenge to which these efforts responded. Plague, in sum, broke the Malthusian deadlock of the thirteenth century, which threatened to hold Europe in its traditional ways for the indefinite future … The great population debacle of the late Middle Ages did not, in sum, introduce an entirely new demographic system. But it did redistribute the population between the two tiers of the traditional system. Depopulation gave access to farms and remunerative jobs to a larger percentage of the population. High wages and low rents also raised the standard of living for substantial numbers. They became acquainted with a style of life that they or their children would not want easily to abandon. For a significantly larger part of society, the care of property and the defense of living standards were tightly joined with decisions to marry and to reproduce. Presumably, these are the origins of the demographic system which Wrigley and Schofield find already functioning in sixteenth-century England. Out of the havoc of plague, Europe adopted what can well be called the modern Western mode of demographic behavior … The great population debacle of the late Middle Ages did not, in sum, introduce an entirely new demographic system. But it did redistribute the population between the two tiers of the traditional system. Depopulation gave access to farms and remunerative jobs to a larger percentage of the population. High wages and low rents also raised the standard of living for substantial numbers. They became acquainted with a style of life that they or their children would not want easily to abandon. For a significantly larger part of society, the care of property and the defense of living standards were tightly joined with decisions to marry and to reproduce. Presumably, these are the origins of the demographic system which Wrigley and Schofield find already functioning in sixteenth-century England. Out of the havoc of plague, Europe adopted what can well be called the modern Western mode of demographic behavior.

The Black Death opened the way for freer markets and the Industrial Revolution, the fruits of which dramatically improved well-being around the world. That will be the subject of the next essay in this series.