Continuing our essay series on Brian Villmoare’s “Big History” book The Evolution of Everything: The Patterns and Causes of Big History, this essay will explore how, as governments became freer, so did economies.

Following the fall of the Roman Empire, early governmental hierarchies in Europe developed into a system called “feudalism.” As Villmoare writes:

Once humans formed complex agrarian societies, naturally the economic systems became more complex. The hierarchical nature of these societies, with a few powerful individuals at the top, and a much larger set of poorer and less powerful people below, is reflected in (and largely caused by) their economic system. This economic system is known as feudalism. Under this system, land became owned, and this owned land (private property) was consolidated by the powerful. But empty land is not productive unless there are people to work on it, so poor people were granted the right to live on the land and grow crops, but only under the condition that they give a proportion of their crops to the landowner. This lifestyle could work out well for both the powerful landowners and the working farmers, if the harvest was good and the landowner didn’t demand too much of the food grown. Alternatively, it could be very exploitative – the landowners typically controlled the armed forces and could enforce compliance to any decisions they made. And if the harvest was poor, and the landowners demanded a fixed amount of crops, there might not be enough left over for the farmers to feed themselves. A critical element missing in this system was free choice at the individual level. Although an individual (peasant or serf) working the land could, in theory, make a choice to leave one landowner and look for a better deal elsewhere, in practice this was often not possible. Landowners would use various methods to prevent the peasants from having choices – colluding together on how much of the harvest to take as rent, or, in the case of pre-Soviet Russia, simply passing laws forbidding the serfs from moving away from one landowner without specifically granted permission … [T]he power disparities made the system inherently exploitative, and there have been occasional peasant revolutions throughout history to protest the abuses of the peasantry by landowners. None of these were successful in generating any long-term systematic changes because, over time, if new people were put in charge, exploitation would ultimately rear its head again … However, feudalism only ever shifts the wealth in a country from one part to the other. Generally, the wealth of the country would accumulate in the higher levels of the system – the landowners, who retained the right of choice. But there was a fixed amount of wealth in the system of a country, so in financial terms there was no growth in the economy. The leaders of some countries realized that they had excess production. A natural way to dispose of this excess is to trade it with other countries.

“Feudalism” then transformed into “mercantilism”:

The government controlled the exports, so, for the individual peasant, the result was much the same, although the introduction of additional wealth into the overall economic system might benefit the worker incidentally. In this system, the aspect of choice is still relatively constrained – crops are not sold on an open market because the government controls all trade and makes the choices. This system is known as mercantilism, and it appears when governmental power is strong enough that it can control the landowners and regulate the production and trade of the country … Under this system, in which governments control trade, there are economic incentives to control land that produces trade. The European period of mercantilism is when we see colonies established by many European countries. Advances in sailing technology had made long-distance ocean trade practical, so controlling far-off lands that produced resources for trade to other countries became realistic for the first time. This is the period when we see the appearance of special government-regulated monopolies that were, essentially, extensions of governmental policy. There were many: the Dutch East India Company, British East India Company, French East India Company, Swedish East India Company, South Sea Company, Sierra Leone Company, German New Guinea Company, etc. In all of these organizations, the government gave a monopoly to a company for the purposes of establishing a colony. The output of the company was to be regulated by, and directly benefit, the government of the country (notably Massachusetts and Virginia were founded this way), but the general manner and method of generating that output was left to the companies … Ultimately, the exploitative aspects of mercantilism were its undoing. Perhaps the most famous rejection of the government monopoly on trade in the United States was the Boston Tea Party in 1773. The government-issued charters of the British colonies on the eastern side of North America imposed strict rules on the importation amounts and taxes imposed on tea (which had been produced in another British colony in India). The colonial citizens were expected to buy a certain amount of tea and to pay a certain tax. Mercantile rules meant that the citizens of Massachusetts were not permitted to purchase tea from any other source. This lack of free choice at the level of the individual market participant in the tea marketplace, and resentment at the taxes, is what inspired some of the rowdier citizens of Boston to storm aboard a tea-trading ship and toss the tea overboard.

Rebellion against mercantile exploitation championed the competition of free enterprise over governmental control over who can produce what:

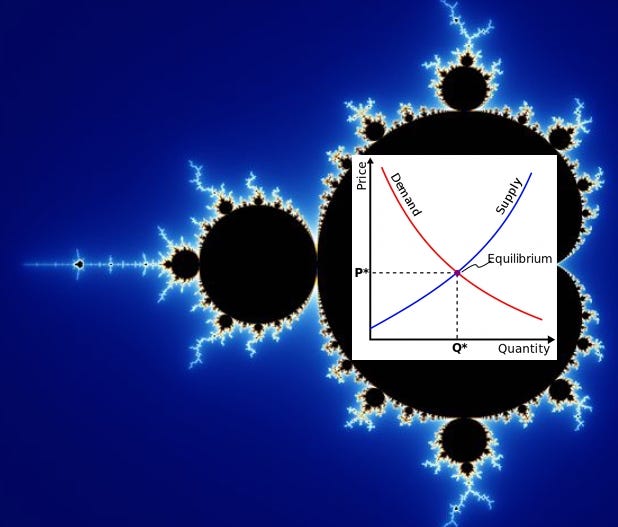

Some of the impetus for the change in economic models came from the highly influential economic theorist Adam Smith (1723–1790), who argued that mercantilism was constraining economic growth. He proposed that economies could not reach their true potential until government monopolies (the mercantile companies) were revoked. He argued that a true “open market,” in which all individuals were free to make choices about economic decisions, would result in an equilibrium that would maximize wealth and political power for all. One of the critical ideas was his idea of competition: when two companies were permitted to compete, each would have to improve, either by producing better products or selling them at a lower price. When companies had to compete for workers, they would have to offer better wages or working conditions. The ultimate outcome of all of this competition would be a marketplace with the best possible combination of quality goods at low prices, with well-compensated workers.

Free markets of this sort, combined with the technological innovations of the Industrial Revolution, greatly improved people’s quality of life:

Although we often think of industrial workers as being exploited during the first century of the Industrial Revolution, it is clear that factory work created economic and political power for many of the workers. The demand for factory workers was strong, and this was the first time that women entered the public marketplace in large numbers. Previously, women had made substantial contributions to the economy with their work on family farms and family businesses. But in those cases, the income was tied to the family, and the women, although contributing to the income, were not part of the public marketplace. But once women were working in factories, they acquired income independent of any family farm or business. A woman could be single, living alone, and still make a reasonable salary. Disentangled from the economic dependencies of a family farm or business, women became a significant economic and political force for the first time. This is the period in which the call for the women’s rights became a significant public issue, and marks the appearance of the right to vote for the first time in most of the Western world … It is worth noting that, in the developing world today, factory work is still a route out of rural poverty for women seeking to avoid oppression by conservative and patriarchal traditions. In these places, women can obtain economic power and independence for the first time, and the empowerment of women is most often found in countries with industrial rather than rural economies … One consequence of the industrialization of agriculture, as well as the ready availability of jobs in the cities, is that the populations of many countries shifted from predominantly rural to predominantly urban. In the USA, at the end of the eighteenth century, only 5 percent Americans lived in cities, but by the end of the nineteenth century that had multiplied seven times over, so that 35 percent were living in urban areas. That trend continues, and today more than 75 percent of Americans live in or near a city. The lack of farm workers was no impediment to crop production – despite the migration away from rural areas, per-acre crop production grew more than sevenfold from the early nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century … [F]amines, which were once common across the world, are virtually unheard of in industrialized nations … Today, people live, on average, more than twice as long as they did in 1720, thanks in significant part to industrialized agriculture … To keep factories fully staffed, factory owners had to pay competitive wages, and hired men and women (and children, initially) in increasingly higher numbers. Often, poorer communities benefited substantially, and manufacturing employment became a path to the new middle class … Many of the political struggles of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were between the competing interests of the industrialist class and the working class. Populations in industrialized cities soared, as people fled rural life for the economic opportunities of factory work. At the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, more than 90 percent of people lived on farms in rural settings. By the end, in the twentieth century, most people in industrialized nations lived in or around cities … Because of the need for engineers and scientists to drive the technology of production forward, education became a priority in industrialized countries. Many colleges, universities, and libraries were established during this time, often with the economic support of the new industrialists, as the world could now see the value of an educated populace. Illiteracy rates dropped and became relatively rare by the latter twentieth century in developed nations … Economics, simply put, is the systematic study of choices. It is a way of understanding why things behave the way they do. When biologists look at why elk are distributed across certain patches of a mountain range, an economic perspective would examine the costs of movement (in, say, calories), against the benefit of the food availability. Elk will normally take shorter routes to denser patches of food, and that is consistent with an economic perspective on behavior. Similarly, when a wolf decides whether or not to try and kill a young elk in a herd, she is judging the risk of being injured or killed by the mother elk against the benefit of the meat that young elk represents. Certain circumstances will change her calculations – the hungrier the wolf, the more important it is for her to eat, which may have an effect on her economic calculations of risk/reward … The same logic applies at the individual scale. People make decisions based on their perceptions of risks and rewards, and economists use their understandings of human behavior to try to figure out why they did what they did, and what they will do in the future … One of the underlying premises of economics is that individuals are making choices. Normally, we tend to think of humans as acting rationally, making decisions that are appropriate to their specific circumstances. (Of course, what people may think of as a rational decision may in fact not actually be, potentially because of genetic predispositions to act on short-term gains at the cost of long-term losses or because of cultural beliefs.) So economists try to understand why a rational actor would make a given decision in a given circumstance, and, in turn, how many millions of decisions, by millions of actors, affect the world.

Societies came to realize that the uncertainties of human decisions on a large scale required economic freedom. As Villmoare explains:

Any billiards player is familiar with the problems presented by chaos theory. When the cue ball (white) is struck against a single ball, if it is hit within a certain range of spots, it will predictably go into the pocket. However, in combination shots, the imprecision increases with each ball struck. Some slight changes alter the angle of the final ball to a minor degree, but with other slight changes, the final ball might be missed altogether. So the result is not necessarily proportional to the variation in the inputs …

That dynamic applies to complex weather systems such that “Meteorologists can predict the weather with some degree of precision only about four days out.”

And so with human behavior:

The unpredictability of systems with large numbers of interacting parts is one of the reasons predicting human behavior is so difficult. The human brain has roughly 90 billion neurons and some 200 million connecting circuits (called axons). In each human, the neurons and axons are wired in unique ways not found in any other human (even an identical twin). This is one of the reasons predicting the response of any one human to specific circumstances is so difficult.

And that’s why we need free economies. As Villmoare writes:

[T]he chaotic nature of economic systems is one of the major reasons why true command-style communism does not work. National economic systems are very complex, with millions of interacting parts. There are millions of workers, and each of those workers, in addition to contributing to the production of the economy, are consumers of the products of the economy. Each worker needs clothing, food, housing, medicine, transportation, and leisure. In a communist command economy, a single controlling power attempts to make all of the decisions for the economy. They try to determine what every citizen requires (in terms of food, clothing, transportation, etc.), and then allocates material and labor resources to meet those needs. So, for example, to make cars the central authority determines the demand for cars, and then decides how much steel, rubber, copper, plastic, and aluminum, as well as the various types of skilled labor, to allocate to meet the demand. Decisions about the manufacturing process are also made high in the control system. This is done for literally every single product in the economy – how many shoes, and how many of each size, and for each shoe type and style. But the problem is that those few individuals are like the pool player hitting the cue ball in a huge combination shot. There is a degree of inaccuracy at each scale of the process, and those errors accumulate down the many layers of the system, so that at the end there is a considerable mismatch between consumer need and the product released. Without individuals at every level of the process correcting the mismatch between the availability of materials, resources, and demand, the errors accumulate enough to make the economic system extremely inefficient. This inefficiency was one of the major reasons why communism in the Soviet Union failed … Classical free market economics [on the other hand] follows a pattern that shows emergent complexity. Much like the birds, the actors in a free market economy are making individual decisions that are appropriate for their specific circumstance, and in this way the economy is largely self-correcting. As circumstances change within any one part of the economy, the individuals involved in their businesses (small and large) make individual decisions to maximize their benefit and minimize their risk. Because these people are directly involved with their part of the economy, they tend to be relatively well informed. This pattern, of well-informed self-interest, makes the actions of others relatively predictable. As individuals (and businesses) at all levels of production and consumption follow the general rule of “maximize self-interest,” the overall economy tends to be very efficient. This makes free market economies relatively flexible and able to respond rapidly to changes in demand or resource availability. Because there are normally multiple companies in competition (in price and quality), there is a constant refining of methods, increasing efficiency. Further, companies are in competition for the best and most innovative workers. From this enormous pool of self-interested, well-informed, and free-acting individuals and companies, we find that overall more people are economically better off, and there is a steady growth in the economy. So from a large pool of independent individuals all acting in their own self-interest, economic growth and health emerges … It is far too complex to try to understand every decision by every individual across the world. So in order to make sense of these economic decisions, we tend to frame them within systems, which have evolved over time. Capitalism Choice at a nongovernmental level is the key element of the capitalist system. In a modern economy, of course, we are not acting as hunter-gatherers simply exchanging fish for arrowheads. In the modern economic system, products must be manufactured from raw materials and then sold. So in a capitalist system, at every stage of the process, choice plays a key role. For example, in the manufacture of hats, the wool manufacturer offers wool at a particular price. The hat manufacturer may accept the price, or reject it and look elsewhere. Once wool is purchased, the workers in the factory may accept their jobs at the salary and working conditions offered, or they may quit and take jobs with better circumstances. Once the hats are manufactured, they must be trucked to the shops by drivers who either accept the trucking job or reject it based on the wages offered. At the shop, the sales people will also accept or reject their jobs. Finally, once the hats are on the shelf of the haberdashery, the consumer may choose to buy the hat (if it is offered at a good price and is made in the latest style), or they may reject it and buy hats from another manufacturer … In a smoothly running capitalist system, these choices are freely made: the worker has plenty of jobs to choose from, and the manufacturer has plenty of workers to whom they can offer jobs. At the level of the consumer, there are many hats to choose from, and enough consumers that most manufacturers can thrive by offering good hats at reasonable prices.

As Villmoare explains, free market economies, without adequate competition, can lead to power imbalances between employers and workers:

Under some circumstances, the incentive to accept a job may mean the difference between eating and starving. Under those circumstances, unless there are as many acceptable jobs as there are employees to fill them, the incentive favors the employer, who can then offer employment terms favorable to the employer’s priorities; this might mean very low wages and dangerous working conditions.

But as Villmoare writes, the development of overly generous government welfare benefits systems to counteract such dynamics can result in far more harm than good:

[I]f there is a strong social welfare system, people may not be incentivized to work at all. If you can get as much money from welfare as you would in a job, there is no incentive to take a job, even if there are sufficient jobs for full employment.

Interestingly, some of the perverse incentives created by the provision of benefits by higher authorities have manifested themselves in the evolution of the large variety of dog breeds we have today. Wolves, from whom all dogs are descended, carefully attend to their offspring because they don’t have human owners who will care for their offspring for them. Male dogs, however, have come to depend on their humans owners not just for food, but also for the care of their own puppies. As Gregory Cochran and Henry Harpending write in The 10,000 Year Explosion:

Domesticated animals and plants often look and act very different from their wild ancestors, and in every such case, the changes took place in far less than 100,000 years. For example, dogs were domesticated from wolves around 15,000 years ago; they now come in more varied shapes and sizes than any other mammal … Their behavior has changed as well: … Male wolves pair-bond with females and put a lot of effort into helping raise their pups, but male dogs— well, call them irresponsible … Male wolves help care for their offspring, but male dogs do not. Any adaptation, whether physical or behavioral, that loses its utility in a new environment can be lost rapidly, especially if it has any noticeable cost.

Hopefully, recent policy trends encouraging dependence on government benefits and discouraging work can be reversed. Otherwise, the dramatic progress we’ve made in the quality of life for just about everyone could be lost. As Villmoare writes:

[O]ne thing is clear: since the Industrial Revolution, the free market system has generated the most material wealth for the most people. An average worker today is, in material terms, wealthier and healthier than at any time in history. That is a significant accomplishment, considering that the change has largely occurred in the last 250 years, after almost five millennia of nearly unchanging worldwide feudalism.

Matt Ridley, in his book The Evolution of Everything: How New Ideas Emerged, describes the gradual evolution of free market systems this way:

Prosperity emerged despite, not because of, human policy. It developed inexorably out of the interaction of people by a form of selective progress very similar to evolution. Above all, it was a decentralised phenomenon, achieved by millions of individual decisions, mostly in spite of the actions of rulers. Indeed, it is possible to argue, as Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson do, that countries like Britain and the United States grew rich precisely because their citizens overthrew the elites who monopolised power. It was the wider distribution of political rights that made government accountable and responsive to citizens, allowing the great mass of people to take advantage of economic opportunities … [W]as government the cause of prosperity? In [Adam] Smith’s day, commerce was a tightly regulated business, with joint-stock companies chartered specifically and exclusively by the state to have monopolies, and mercantilist trade policies designed to promote certain kinds of foreign exports, not to mention professions strictly licensed by the government. In the cracks between the paving stones of regulation and dirigisme individuals could buy and sell, but pretty well nobody thought this was the source of prosperity. Wealth meant accumulating precious things. The ‘physiocrats’ in France had at least begun to suggest that productive work was the source of wealth, not heaps of gold. From François Quesnay, leader of the physiocrats, whom he met in 1766, Smith picked up the idea that mercantilist direction of trade was a mistake, as was government grabbing all the revenue of trade to spend on ruinous wars and futile luxuries: their cry was ‘Laissez faire et laissez passer, le monde va de lui même!’ (Let do and let pass, the world goes on by itself!). But the physiocrats insisted, strangely, that the only kind of productive work was farming. Manufacture and services were wasteful frittering. Smith said instead that the ‘annual produce of the land and labour of the society’ was what counted. Today we call that GDP. So becoming more prosperous means the same as becoming more productive – growing more wheat, making more tools, serving more customers. And the ‘greatest improvement in the productive power of labour’, Smith argued, ‘seems to have been the effects of the division of labour’. If the farmer supplies food to the ironmonger in exchange for tools, then both are more productive, because the first does not have to stop work and make a tool badly, while the latter does not have to stop work to till a field badly. Specialisation, accompanied by exchange, is the source of economic prosperity. Here, in my own words, is what a modern version of Smithism claims. First, the spontaneous and voluntary exchange of goods and services leads to a division of labour in which people specialise in what they are good at doing. Second, this in turn leads to gains from trade for each party to a transaction, because everybody is doing what he is most productive at and has the chance to learn, practise and even mechanise his chosen task. Individuals can thus use and improve their own tacit and local knowledge in a way that no expert or ruler could. Third, gains from trade encourage more specialisation, which encourages more trade, in a virtuous circle. The greater the specialisation among producers, the greater is the diversification of consumption: in moving away from self-sufficiency people get to produce fewer things, but to consume more. Fourth, specialisation inevitably incentivises innovation, which is also a collaborative process driven by the exchange and combination of ideas. Indeed, most innovation comes about through the recombination of existing ideas for how to make or organise things. The more people trade and the more they divide labour, the more they are working for each other. The more they work for each other, the higher their living standards. The consequence of the division of labour is an immense web of cooperation among strangers … A woollen coat, worn by a day labourer, was (said Smith) ‘the produce of a great multitude of workmen. The shepherd, the sorter of the wool, the wool-comber or carder, the dyer, the scribbler, the spinner, the weaver, the fuller, the dresser . . .’ In parting with money to buy a coat, the labourer was not reducing his wealth. Gains from trade are mutual; if they were not, people would not voluntarily engage in trade … [T]he free market is a device for creating networks of collaboration among people to raise each other’s living standards, a device for coordinating production and a device for communicating information about needs through the price mechanism. Also a device for encouraging innovation. The market is a system of mass cooperation. You compete with rival producers, sure, but you cooperate with your customers, your suppliers and your colleagues. The question then becomes whether commerce only works if it is perfect. Are semi-free markets better than none? The economist William Easterly is in no doubt that the invisible hand is not Utopia: ‘It is the process of driving out of business the incompetent in favour of the mediocre, the mediocre in favour of the good, and the good in favour of the excellent.’ A glance at economic history makes clear that countries run by and in the interests of merchants have not been perfect, but they have always been more prosperous, peaceful and cultured than countries run by despots … To argue that free commerce leads to more prosperity than government planning is not, of course, to argue that all government should be abolished. There is a vital role for government to play in keeping the peace, enforcing the rules and helping those who need help. But that is not the same as saying government should plan and direct economic activity. Likewise, for all its virtues, commerce is not perfect. It has a habit of encouraging wasteful and damaging extravagances, not least because it leads to the marketing of signals for conspicuous consumption … The central problem for systems of command and control, whether fascist, communist or socialist, is the knowledge problem. As champions of free enterprise from Frédéric Bastiat to Friedrich Hayek have pointed out, the knowledge required to organise human society is bafflingly voluminous. It cannot be held in a single human head. Yet human society is organised, none the less. As Bastiat put it in his 1850 Economic Harmonies, how would one even contemplate setting out to feed Paris, a city with hordes of people with myriad tastes? It is impossible. Yet it happens, without fail, every day (and Paris has a still vaster population today, with more eclectic taste in food) … As Deirdre McCloskey puts it, in the great enrichment of the past two hundred years average income in Britain went from about $3 a day to about $100 a day in real terms. That simply cannot be achieved by capital accumulation, which is why she (and I) refuse to use the misleading, Marxist word ‘capitalism’ for the free market. They are fundamentally different things … Far from diminishing, returns kept increasing thanks to mechanisation and the application of cheap energy. The productivity of a worker, rather than reaching a plateau, just kept on rising. The more steel was produced, the cheaper it got. The cheaper mobile phones grew, the more we used them. As Britain and then the world grew more populous, the more mouths there were to feed, the fewer people starved: famine is now largely unknown in a world of seven billion people, whereas it was a regular guest when there were two billion. Even Ricardo’s wheat yields, from British fields that had been ploughed for millennia, began to accelerate upwards in the second half of the twentieth century thanks to fertilisers, pesticides and plant breeding. By the early twenty-first century, industrialisation had spread high living standards to almost every corner of the globe … And the beauty of commerce is that when it works it rewards people for solving other people’s problems. It is ‘best understood as an evolutionary system, constantly creating and trying out new solutions to problems in a similar way to how evolution works in nature. Some solutions are “fitter” than others. The fittest survive and propagate. The unfit die.’ Deirdre McCloskey describes the system that produced the great enrichment of the past two centuries as ‘innovationism’ rather than ‘capitalism’. The new and crucial ingredient was not the availability of capital, but the advent of market-tested, consumer-driven innovation. She locates the cause of the Industrial Revolution in the decentralisation of the production and testing of new ideas: ordinary people were able to contribute to and to choose the products and services they preferred, which drove continuous innovation. For the Industrial Revolution to happen, trial and error had to become respectable. As she put it in a lecture in India in 2014, the enrichment of the poor has resulted not from charity, planning, protection, regulation or trade unions, all of which merely redistribute money, but from innovation caused by markets, which have not been bad for the poor: ‘The sole reliable good for the poor, on the contrary, has been the liberating and the honoring of market-tested improvement and supply.’ … Exchange has the same effect on economic evolution. In a society that is not open to trade, one tribe might invent the bow and arrow, while another invents fire. The two tribes will now compete, and if the one with fire prevails, the one with bows and arrows will die out, taking their idea with them. In a society that trades, the fire-makers can have bows and arrows, and vice versa. Trade makes innovation a cumulative phenomenon. Lack of trade may well be what held back the otherwise intelligent Neanderthals. It is certainly what held back many isolated human tribes in competition with those that could draw upon much wider sources of innovation. Instead of relying on your own village for innovation, you can get ideas from elsewhere. I make use of thousands of brilliant innovations every day. Very few of them were made in my own country, let alone my own village.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore how Western religion contributed to the rise of mass literacy, monogamy, and, ultimately, individualism.