Barriers to Scientific Progress – Part 7

How “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” bureaucracies lower standards at medical schools.

Continuing this essay series on modern barriers to scientific progress, this essay discusses how the sorts of “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” programs described in the previous essay lower standards at medical schools.

These DEI programs, by creating preferences based on race, inherently reduce their emphasis on merit. Standardized tests for medical students are being abandoned because the questions they include do not discriminate in favor of race, contrary to the purpose of DEI programs. As Heather MacDonald writes in the Wall Street Journal:

At the end of their second year of medical school, students take step one of the U.S. Medical Licensing Exam, which measures knowledge of the body’s anatomical parts, functioning and malfunctioning. Topics include biochemistry, physiology, cell biology, pharmacology and the cardiovascular system. High scores on step one predict success in a residency; highly sought-after residency programs, such as surgery and radiology, use exam scores to help select applicants. But some students complain that the pressure to score well inhibits them from “antiracism” advocacy. Writing in an online forum, a fourth-year Yale medical student describes how the specter of step one affected his priorities. In his first two years of medical school, he had “immersed” himself in a student-led committee focused on diversity, inclusion and social justice, and he ran a podcast about health disparities. All that political work was made possible by Yale’s pass-fail grading system for classes, which meant that he didn’t feel compelled to put studying ahead of diversity concerns. Then, step one “reared its ugly head.” Getting an actual grade on an exam might prove to “whoever might have thought it before that I didn’t deserve a seat at Yale as a Black medical student.” The solution was obvious: abolish step-one scores. Since January, the test has been graded on a pass-fail basis. The Yale student won’t have to worry that his studying will cut into his activism. Whether his future patients will appreciate his chosen focus is unclear. Virtually all medical schools admit black and Hispanic applicants with scores on the Medical College Admission Test that would be all but disqualifying if presented by white and Asian applicants, and some schools waive the MCATs entirely for select minority students. Courses on racial justice and advocacy are flooding into medical school curricula; students are learning more about white privilege and less about cell pathology … Such stories are rife. A UCLA doctor says that the smartest undergraduates in the school’s science labs are saying: “Now that I see what is happening in medicine, I will do something else.”

MacDonald writes the following in a more extensive article on the same subject:

The AMA’s [American Medical Association’s] 2021 Organizational Strategic Plan to Embed Racial Justice and Advance Health Equity is virtually indistinguishable from a black studies department’s mission statement. The plan’s anonymous authors seem aware of how radically its rhetoric differs from medicine’s traditional concerns. The preamble notes that “just as the general parlance of a business document varies from that of a physics document, so too is the case for an equity document.” (Such shaky command of usage and grammar characterizes the entire 86-page tome, making the preamble’s boast that “the field of equity has developed a parlance which conveys both [sic] authenticity, precision, and meaning” particularly ironic.) … The U.S. Medical Licensing Exam is a prime offender. At the end of their second year of medical school, students take Step One of the USMLE, which measures knowledge of the body’s anatomical parts, their functioning, and their malfunctioning; topics include biochemistry, physiology, cell biology, pharmacology, and the cardiovascular system. High scores on Step One predict success in a residency; highly sought-after residency programs, such as neurosurgery and radiology, use Step One scores to help select applicants. Black students are not admitted into competitive residencies at the same rate as whites because their average Step One test scores are a standard deviation below those of whites. Step One has already been modified to try to shrink that gap; it now includes nonscience components such as “communication and interpersonal skills.” But the standard deviation in scores has persisted. In the world of antiracism, that persistence means only one thing: the test is to blame … The Step One exam has a further mark against it. The pressure to score well inhibits minority students from what has become a core component of medical education: antiracism advocacy. A fourth-year Yale medical student describes how the specter of Step One affected his priorities. In his first two years of medical school, the student had “immersed” himself, as he describes it, in a student-led committee focused on diversity, inclusion, and social justice. The student ran a podcast about health disparities. All that political work was made possible by Yale’s pass-fail grading system, which meant that he didn’t feel compelled to put studying ahead of diversity concerns. Then, as he tells it, Step One “reared its ugly head.” Getting an actual grade on an exam might prove to “whoever might have thought it before that I didn’t deserve a seat at Yale as a Black medical student,” the student worried. The solution to such academic pressure was obvious: abolish Step One grades. Since January 2022, Step One has been graded on a pass-fail basis. The fourth-year Yale student can now go back to his diversity activism, without worrying about what a graded exam might reveal. Whether his future patients will appreciate his chosen focus is unclear … In 2021, the average score for white applicants on the Medical College Admission Test was in the 71st percentile, meaning that it was equal to or better than 71 percent of all average scores. The average score for black applicants was in the 35th percentile—a full standard deviation below the average white score. The MCATs have already been redesigned to try to reduce this gap; a quarter of the questions now focus on social issues and psychology. Yet the gap persists. So medical schools use wildly different standards for admitting black and white applicants. From 2013 to 2016, only 8 percent of white college seniors with below-average undergraduate GPAs and below-average MCAT scores were offered a seat in medical school; less than 6 percent of Asian college seniors with those qualifications were offered a seat, according to an analysis by economist Mark Perry. Medical schools regarded those below-average scores as all but disqualifying—except when presented by blacks and Hispanics. Over 56 percent of black college seniors with below-average undergraduate GPAs and below-average MCATs and 31 percent of Hispanic students with those scores were admitted, making a black student in that range more than seven times as likely as a similarly situated white college senior to be admitted to medical school and more than nine times as likely to be admitted as a similarly situated Asian senior … [S]ome medical schools offer early admissions to college sophomores and juniors with no MCAT requirement, hoping to enroll students with, as the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai puts it, a “strong appreciation of human rights and social justice.” The University of Pennsylvania medical school guarantees admission to black undergraduates who score a modest 1300 on the SAT (on a 1600-point scale), maintain a 3.6 GPA in college, and complete two summers of internship at the school. The school waives its MCAT requirement for these black students; UPenn’s non-preferred medical students score in the top one percent of all MCAT takers. According to race advocates, differences in MCAT scores must result from test bias. Yet the MCATs, like all beleaguered standardized tests, are constantly scoured for questions that may presume forms of knowledge particular to a class or race. This “cultural bias” chestnut has been an irrelevancy for decades, yet it retains its salience within the anti-test movement. MCAT questions with the largest racial variance in correct answers are removed. External bias examiners, suitably diverse, double-check the work of the internal MCAT reviewers. If, despite this gauntlet of review, bias still lurked in the MCATs, the tests would underpredict the medical school performance of minority students. In fact, they overpredict it—black medical students do worse than their MCATs would predict, as measured by Step One scores and graduation rates. (Such overprediction characterizes the SATs, too.) … The medical school curriculum itself needs to be changed to lessen the gap between the academic performance of whites and Asians, on the one hand, and blacks and Hispanics, on the other. Doing so entails replacing pure science courses with credit-bearing advocacy training. More than half of the top 50 medical schools recently surveyed by the Legal Insurrection Foundation required courses in systemic racism. That number will increase after the AAMC’s [Association of American Medical Colleges’] new guidelines for what medical students and faculty should know transform the curriculum further. According to the AAMC, newly minted doctors must display “knowledge of the intersectionality of a patient’s multiple identities and how each identity may present varied and multiple forms of oppression or privilege related to clinical decisions and practice.” Faculty are responsible for teaching how to engage with “systems of power, privilege, and oppression” in order to “disrupt oppressive practices.” Failure to comply with these requirements could put a medical school’s accreditation status at risk and lead to a school’s closure … Advocates of antiracism training never explain how fluency in intersectional critique improves the interpretation of an MRI or the proper prescribing of drugs. Despite the persistent academic skills gap, a minority hiring surge is under way. Many medical schools require that faculty search committees contain a quota of minority members, that they be overseen by a diversity bureaucrat, and that they interview a specified number of minority candidates … Cancer grant applications must now specify who, among a lab’s staff, will enforce diversity mandates and how the lab plans to recruit underrepresented researchers and promote their careers. As with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Freeman Hrabowski scholarships, an insufficiently robust diversity plan means that a proposal will be rejected, regardless of its scientific merit. Discussions about how to beef up the diversity section of a grant have become more important than discussions about tumor biology, reports a physician-scientist. “It is not easy summarizing how your work on cell signaling in nematodes applies to minorities currently living in your lab’s vicinity,” the researcher says. Mental energy spent solving that conundrum is mental energy not spent on science, he laments, since “thinking is always a zero-sum game.” A lab’s diversity gauntlet has just begun, however. The NIH insists that participants in drug trials must also match national or local demographics. If a cancer center is in an area with few minorities, the lab must nevertheless present a plan for recruiting them into its study, regardless of their local unavailability. Genentech, the creator of lifesaving cancer drugs, held a national conference call with oncologists in April 2022 to discuss products in the research pipeline. Half of the call was spent on the problem of achieving diverse clinical trial enrollments, a participant reported. Genentech admitted to having run out of ideas … In May 2022, a physician-scientist lost her NIH funding for a drug trial because the trial population did not contain enough blacks. The drug under review was for a type of cancer that blacks rarely get. There were almost no black patients with that disease to enroll in the trial, therefore. Better, however, to foreclose development of a therapy that might help predominantly white cancer patients than to conduct a drug trial without black participants … The proponents of the systemic racism hypotheses are making a large bet with potentially lethal consequences. In accordance with the idea that racism causes racial health disparities, they are changing the direction of medical research, the composition of medical faculty, the curriculum of medical schools, the criteria for hiring researchers and for publishing research, and the standards for assessing professional excellence. They are substituting training in political advocacy for training in basic science. They are taking doctors out of the classroom, clinic, and lab and parking them in front of antiracism lecturers. Their preferential policies discourage individuals from pariah groups from going into medicine, regardless of their scientific potential … Higher rates of Covid fatalities among blacks is the latest favored proof of medical racism, amplified by a 2022 Oprah Winfrey and Smithsonian Channel documentary, The Color of Care. State and federal health authorities gave priority to minorities in vaccination and immunotherapy campaigns, however, and penalized the highest risk group—the elderly—simply because that group is disproportionately white. Those are not the actions of white supremacists. The likelier reasons for disparities in Covid outcomes are vaccine hesitancy and obesity rates. When the constant refrain about medical racism intensifies vaccine resistance among blacks, the widened mortality gaps will be used to confirm the racism hypothesis, in a vicious circle … America’s very real history of structural racism, a history that took us too long to remedy, resulted in segregated hospitals and cruel disparities in treatment. That past is belatedly but thankfully behind us. The scientific method is a natural corrective to such fatal errors. Now, tragically, when it comes to the contention that racism is the defining trait of the medical profession and the source of health disparities, opposing views have been ruled out of bounds and are grounds for being purged.

As Ira Stoll writes in the Wall Street Journal:

To see how the diversity, equity and inclusion mania is colliding with meritocracy in American higher education, pay attention to the flap over graduate schools pulling out of the U.S. News rankings. Readers who aren’t applying to medical school may have missed the controversy. But anyone who plans on seeing a doctor or benefiting from research or treatment at an academic medical center has an interest in the outcome. So far, U.S. News has resisted demands from the graduate schools to base the rankings on equity rather than on the grades and test scores of incoming students. U.S. News has been transparent about the method it uses for its rankings, including factors such as a reputation survey, MCAT scores and grade point averages of incoming students. The medical schools have been similarly clear about why they disagree with the U.S. News method and will stop participating. The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in a Jan. 24 statement, said the U.S. News rankings undermine the school’s “commitment to anti-racism” and “outreach to diverse communities.” “Diversity, equity and inclusion are important factors in our decision,” the school’s deans, Dennis Charney and David Muller, said. “We believe that the quality of medical students and future physicians is reflected in their lived experiences, intersecting identities, research accomplishments, commitment to social and racial justice, and a set of core values that are aligned with those of our school.” The statement went on, “The U.S. News rankings reduce us to a number that does not do justice to these profoundly important attributes, instead perpetuating a narrow focus on achievement that is linked to reputation and is driven by legacy and privilege.” The dean of Stanford Medical School, Lloyd Minor, made a similar claim, announcing that instead of participating in the U.S. News rankings, the school would start issuing its own data “emphasizing diversity, equity, and inclusion.” A Jan. 24 statement from the dean of the medical school at the University of Pennsylvania, J. Larry Jameson, complained that the U.S. News rankings “measure the wrong things” and “encourage the acceptance of students based upon the highest grades and test scores.” U.S. News already does provide a list ranking universities that have the most racial and ethnic diversity among students. The medical school deans and the activists pushing them, however, apparently won’t be satisfied until test scores and grades are totally eliminated from the rankings, replaced by a commitment to anti-racism and diversity, equity and inclusion, which are less easily quantified. When colleges started making the SAT optional, some of us shrugged and said, well, that’s fine, so long as they don’t eliminate the tests for would-be brain surgeons. Now the battle lines have shifted in the meritocracy wars so that it’s precisely would-be brain surgeons whose test scores the medical schools want to conceal. The businessmen for whom these medical schools are named—Carl Icahn, Raymond Perelman, P. Roy Vagelos—could never have amassed the fortunes they did if they ran their companies based on vague diversity commitments rather than quantifiable financial results … But the U.S. News fight goes beyond that. It exemplifies a debate about the definition of excellence. Is the measure of quality doing better in school and on tests? Or is it having the correct representation of skin color, suitably impoverished background and ideological commitment? Sure, being a good doctor is more complicated than a test score. Softer skills, such as empathy, listening and relationship-building, matter. But advances in health and high-quality care also depend on measurable intellectual rigor. If that is abandoned in favor of trendy ideological conformity, the consequences for higher education, for patients and for the nation could be deadly.

The medical school at the University of California, San Francisco, requires a course in political advocacy. As reported in the Free Beacon:

On November 16, 2023, just before 8:00 a.m., hundreds of pro-Palestinian protesters formed a human chain across the San Francisco Bay Bridge, blocking all westbound traffic and trapping tens of thousands of vehicles in a five-mile backup. Among those vehicles were three trucks associated with the University of California, San Francisco, health system. Each was transporting organs that were set to be transplanted later that day, and the couriers, who had budgeted just 30 minutes of travel time, had their arrival delayed by nearly four hours. The holdup forced UCSF to postpone pressing operations and put organ recipients at greater risk. "Every minute of time on ice is hard for the organs," Garrett Roll, a UCSF transplant surgeon, told the San Francisco Chronicle at the time, adding that organs function less well for patients the longer they remain in transit. Twenty-six demonstrators were ultimately charged, eight of them with felonies. UCSF is the second-largest transplant center in the United States and home to one of the top medical schools in the world. Given the stakes—an unlawful protest had impeded the very sort of surgeries that the hospital specializes in—one might expect the school to condemn that protest and discourage students from emulating it. But that is not what UCSF did. In a mandatory six-week unit on "Justice and Advocacy in Medicine," which covers "issues like racism, ableism, and patriarchy," the school told first-year medical students this year that the protest on the bridge was an example of "direct action," akin to "sit-ins" or "vigils," that disrupt "business as usual" to "pressure targeted decision-makers." … The unit takes up six full weeks of class—more than the amount of time spent on basic anatomy or cardiovascular health, according to UCSF’s summary of the first-year curriculum—and describes "objectivity" and "urgency" as characteristics of "white supremacy culture." In one slide deck presented as part of the course, UCSF says students should "consider reporting" those traits, though it does not indicate to whom. The characteristics of white supremacy culture also include "individualism" and "perfectionism," according to the slides, which depict each trait as a bottle of poison.

Jeffrey Anderson reports on how, in pursuit of political, not scientific, ends, even Scientific American magazine has come to explicitly reject “prioritizing scientific rigor” in the pursuit of knowledge:

Scientific American, which dates to 1845 and touts itself as “the oldest continuously published magazine in the United States,” recently ran an article arguing that scientists should prioritize “reality” over scientific “rigor.” What would make a publication with a name like this one set empirical evidence at odds with reality? Masks, of course. Naomi Oreskes, a Harvard professor of the history of science, argued that by “prioritizing scientific rigor” in its mask studies, the Cochrane Library may have “misled the public,” such that “the average person could be confused” about the efficacy of masks. Oreskes criticized Cochrane for its “standard … methodological procedures,” as Cochrane bases its “findings on randomized controlled trials, often called the ‘gold standard’ of scientific evidence.” Since RCTs haven’t shown that masks work, she writes, “[i]t’s time those standard procedures were changed.” City Journal contributing editor John Tierney called Cochrane “the world’s largest and most respected organization for evaluating health interventions.” A recent Cochrane review found that “[w]earing masks in the community probably makes little or no difference to the outcome of influenza-like illness (ILI)/COVID-19 like illness”—or “to the outcome of laboratory-confirmed influenza/SARS-CoV-2”—“compared to not wearing masks.” The review also found that “use of a N95/P2 respirators compared to medical/surgical masks probably makes little or no difference” for the “outcome of laboratory‐confirmed influenza infection.” While Oreskes asserts that Cochrane’s findings were made with “low to moderate” certainty, each of the findings quoted above was made with “moderate certainty,” the second-highest of four certainty classifications. “Moderate certainty,” Cochrane notes, means that “the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect.” The Cochrane review’s lead author, Oxford’s Tom Jefferson, said of masks in a subsequent interview with Australian investigative journalist Maryanne Demasi, “There is just no evidence that they make any difference. Full stop.” In response, Oreskes claimed that “[t]he Cochrane finding was not that masking didn’t work but that scientists lacked sufficient evidence of sufficient quality to conclude that they worked.” She continues, “Jefferson erased that distinction, in effect arguing that because the authors couldn’t prove that masks did work, one could say that they didn’t work. That’s just wrong.” But Jefferson didn’t simply say that masks don’t work; he said there’s “no evidence” they work. The burden of proof should be on the side of those advocating a medical intervention.

Some critiques have been made regarding the Cochrane study, but the most prominent of them appears to be filled with errors, as Jesse Singal has reported.

As the Wall Street Journal editorialized on the issue of DEI program influence on American medical schools:

The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) is a nonprofit based in Washington, D.C., that represents and advises medical schools. It also has influence with the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, the national accreditor that sets med-school standards. So when the AAMC tells schools to revise how they teach, America’s future physicians will be obliged to listen. The AAMC recently released a report describing the new “diversity, equity and inclusion competencies” that medical students and residents will be expected to master. Practicing physicians who work at teaching hospitals may also soon be required to undergo this form of, well, political re-education. As a starting point, aspiring doctors will have to become fluent in woke concepts such as “intersectionality,” which the AAMC defines as “overlapping systems of oppression and discrimination that communities face based on race, gender, ethnicity, ability, etc.” Med students who managed to avoid learning critical race theory in college will now get an immersive course. They will also be expected to demonstrate “knowledge of the intersectionality of a patient’s multiple identities”—not to be confused with personality disorders—and “how each identity may result in varied and multiple forms of oppression or privilege related to clinical decisions and practice.” This sounds as if every medical diagnosis will have to be made with an accompanying political and sociological analysis … Most young people who pursue a career in medicine want to help patients. Now they will be taught that “an intricate web of social, behavioral, economic, and environmental factors, including access to quality education and housing, have greater influence on patients’ health than physicians do,” AAMC leaders write in a StatNews op-ed trumpeting their new woke curriculum … AAMC leaders write further in StatNews that “we believe this topic deserves just as much attention from learners and educators at every stage of their careers as the latest scientific breakthroughs.” That sounds dangerous. Will learning about mRNA technology or the latest treatment for melanoma take a back seat to new theories of cultural appropriation? America faces a looming and severe doctor shortage as baby boomers retire. It won’t help attract prospective doctors to tell top students they must attend to their guilt as racial and political oppressors before they can diagnose your cancer.

(Recall also how the medical committees charged with coming up for a plan for COVID vaccine distribution originally recommended that certain people be given priority in receiving the vaccine, based on race, over those in the more vulnerable older population.)

As the Free Beacon reports:

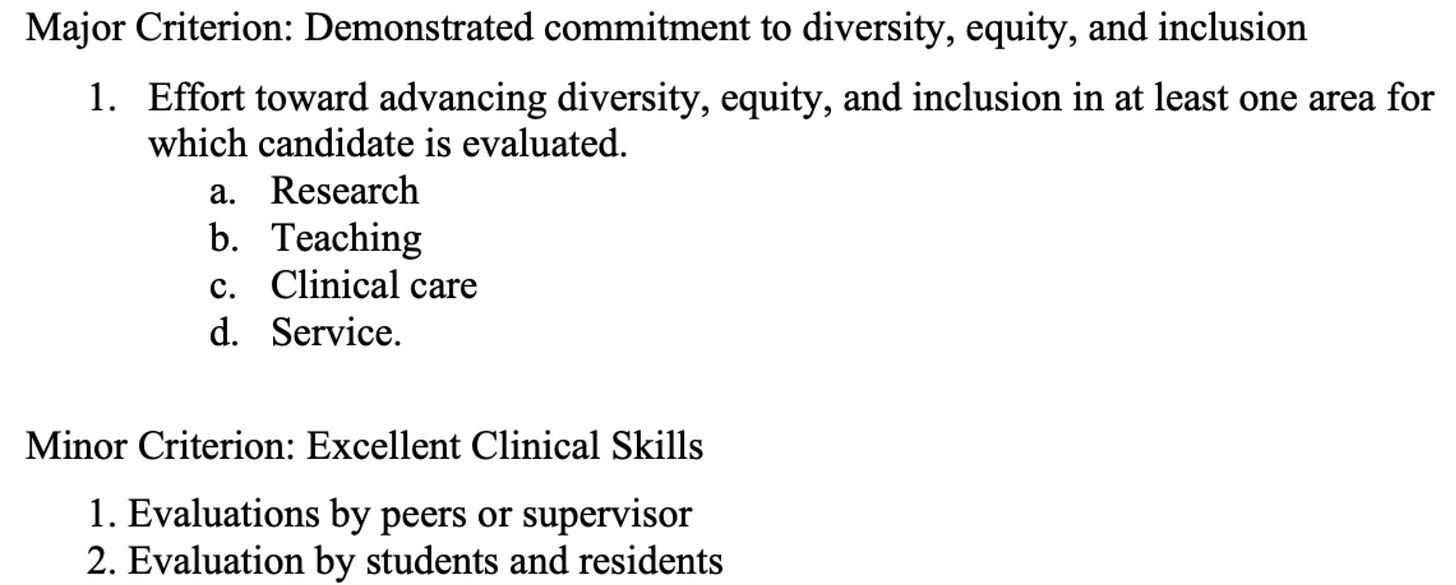

Brown University Medical School now gives "diversity, equity, and inclusion" more weight than "excellent clinical skills" in its promotion criteria for faculty, raising questions about the quality of teaching and patient care at the elite medical school and underscoring how deeply DEI has penetrated medical education. The criteria, which are posted on Brown’s website and have not been previously reported, list a "demonstrated commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion" as a "major criterion" for all positions within the Department of Medicine, which oversees the bulk of the school’s clinical units. Clinical skills, by contrast, only count as a "minor criterion" for many roles.

Doctors who reviewed the criteria were alarmed, saying they reflect an unusually frank admission that merit is taking a back seat to DEI. "This is as stark as it gets," said Bob Cirincione, an orthopedic surgeon in Hagerstown, Maryland. The criteria "say what DEI in medical schools is all about. And it’s not about clinical performance." Hector Chapa, a clinical professor at Texas A&M College of Medicine, said it was "difficult to comprehend" why clinical skills get less weight than DEI. "That is heartbreaking," Chapa told the Washington Free Beacon. "Clinical skills are of paramount importance and should be considered major criteria for any promotion."

While DEI programs devalue merit in their evaluative criteria, the patients of doctors who scored better on their board certification exams tend, not surprisingly, to have higher survival rates. As reported by the Harvard Medical School:

A new study, published May 6 in JAMA, found that internal medicine patients of newly trained physicians with top scores on the board certification exam — a comprehensive test usually taken after a physician completes residency training — had lower risk of dying within seven days of hospital admission or of being readmitted to the hospital. The analysis was led by researchers at Harvard Medical School and the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), the body that developed and regularly updates the exam that qualifies a physician as an internal medicine specialist. Some of the study authors, including lead author Bradley Gray, are employed by ABIM. The findings, the team said, provide reassurance that the board exams in internal medicine are reflective of future physician performance on critical indicators of patient care and outcomes. “These results confirm that certification exams are measuring knowledge that directly translates into improved outcomes for patients,” said study senior author Bruce Landon, professor of health care policy at HMS and an internal medicine doctor at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. In particular, the researchers found that “top vs bottom examination score quartile was associated with a significant 8.0% reduction in 7-day mortality rates (95% CI, −13.0% to −3.1%; P = .002) and a 9.3% reduction in 7-day readmission rates (95% CI, −13.0% to −5.7%; P < .001).”

As a result of all this, I’ve heard from a doctor at a medical school that “I know no academic of my cohort who will see any physician under 45 or 50 for just these reasons (unless we have trained them) … These are far more immediate effects than long-term diminution of science research … And they likely contribute to the ever rising ‘excess deaths’ numbers we are seeing. These are big, big deals.”

Incidentally, research has also shown that the business investment equivalent of DEI programs, known as “ESG” investing (which stands for “Environmental, Social, and Governance”) also reduce standards for performance, to the detriment of investors. As a former chief economist at Nasdaq writes in the Wall Street Journal:

Capitalists invest money, and manage companies, to do well financially. Proponents of so-called woke capitalism claim that companies can do “well” financially by doing “good” politically. The idea is that advancing a political agenda will also enhance profits and shareholder returns. Whether this does good is a matter of opinion, but whether it does well can be measured. Woke capitalism makes its way into financial markets through an ill-defined concept known as environmental, social and governance investing. Huge investment managers use their ownership of shares to pressure companies to jump on the ESG train. But while individual investors are free to support whatever causes they wish with their dollars, those who invest other peoples’ money have a fiduciary duty to focus solely on clients’ financial interests. Thus it’s important to know whether politically focused companies actually do produce superior financial results. To answer this question, we used research from 2ndVote Analytics Inc., a company that scores U.S. large-cap and midcap companies on their social and political engagement on five-point scale. Analytics evaluates company data on six social/political issues—the environment, education, abortion, Second Amendment rights, other basic constitutional freedoms and support for a safe civil society—and also generates a composite score. Company scores, updated quarterly, range from 1 (most liberal) to 5 (most conservative), with 3 meaning neutral or unengaged. On average, roughly a quarter (or 221) of the S&P 900 large/mid-cap companies studied scored 3—taking no political or social stance on any of these six issues—during the period from June 30, 2021 (when the data was first available), through Jan. 31, 2023. Of the remaining companies, the political tilt was strongly to the left. More than 59% scored liberal, and under 15% conservative (with only one company higher than 4). We used a neutral score of 3 as a proxy for companies that focus on investors’ returns rather than activism. We then compared the performance of those neutral companies with the market (represented by the S&P 500 and Russell 1000) as well as major ESG-registered funds. The point is to demonstrate how well a portfolio of business-focused politically neutral companies performs compared with those potentially distracted by political issues. In making this comparison, we used a third-party index-calculation agent and market-value weighting in a manner similar to the S&P 500 and Russell 1000 benchmarks (total returns) … The analysis covers the full period for which company scores were available, including the market runup in the last half of 2021, the 2022 bear market and the early-2023 rebound. The results are compelling. The market was down overall, by 1.8% for the S&P 500 and 3.2% for the Russell 1000. ESG funds performed worse, with most losing 2.5% to 6.3%. A simple index composed of only neutral companies gained 2.9%, significantly outperforming both broad-market and ESG indexes in up and down markets. Notably, the benchmarks include the outperforming neutral companies—indicating that the politically active companies further underperformed … The data indicate that, as common sense would suggest, companies that focus on profits outperform companies that don’t.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine several views on how science might be said to flourish, or stagnate, at any given time, and how the principles behind these DEI programs push science toward stagnation or worse under all such views.