A Constitution to Control Government, Drafted by People Who Controlled Their Emotions – Part 3

Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the threat of social media.

This essay continues a series on Jeffrey Rosen’s book The Pursuit of Happiness: How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined America, in which he presents the fascinating story of how the founders of our country liberated a nation by keeping their own spirits in check and crafting a system of checks and balances designed to do the same for America.

As Rosen writes, both Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln shared the Founders’ understanding that self-restraint was necessary for personal success. As Rosen writes of Frederick Douglass:

About the age of thirteen, around 1831, [Douglass, while still a slave] saved up enough to buy, for fifty cents, a “very popular school book, viz: the Columbian Orator.” The book changed his life. “Every opportunity I got, I used to read this book.” The Columbian Orator was indeed “very popular.” Published in twenty-three editions between 1797 and 1860, it sold about two hundred thousand copies and, along with the Bible, was among the only books in many nineteenth-century homesteads. In addition to teaching principles of eloquence and oratory, The Columbian Orator offered nineteenth-century schoolchildren what Douglass called a “rich treasure” of primary texts, to be read aloud. It included excerpts from the speeches and writings of many of the philosophers that inspired Franklin and Jefferson in their writings about the pursuit of happiness, including Cicero, Socrates, Milton, and Cato’s Letters. It also included a selection from Benjamin Franklin’s poetry, as well as a eulogy in Paris praising Franklin for his time management and industry and calling Poor Richard’s Almanack a “catechism of happiness for all mankind.”

As for Abraham Lincoln, Rosen writes:

Lincoln was also inspired by other popular “readers”—nineteenth-century anthologies of classical and Enlightenment rhetoric—including Murray’s English Reader. “Mr. Lincoln told me in later years that Murray’s English Reader was the best school-book ever put into the hands of an American youth,” his law partner, William Herndon, recalled. Like The Columbian Orator and Poor Richard’s Almanack, Murray’s English Reader sampled from the highlights of classical and Enlightenment moral philosophy, presenting them in easily digestible maxims that provide a guide for how to develop good character. If Franklin, Washington, Madison, and Hamilton learned the importance of self-mastery and self-control from Cicero and Addison’s Spectator, Lincoln and Douglass learned the same lessons from the Cicero and Addison excerpts in Bingham’s and Murray’s readers. Douglass distilled the lessons of the ancient wisdom in his “Self-Made Men” speech, which he delivered for more than three decades after his historic escape from slavery in 1838. Written before the Civil War, the speech became Douglass’s most frequently requested address during the Reconstruction era, as Douglass himself became its American prototype. Self-made men, Douglass said, were “men of work,” and “honest labor faithfully, steadily and persistently pursued, is the best, if not the only, explanation of their success.” Moreover, Douglass emphasized, the capacity for hard work was in everyone’s grasp. “[A]llowing only ordinary ability and opportunity, we may explain success mainly by one word and that word is Work! Work!! Work!!! Work!!!!” Douglass exhorted. In Douglass’s view, all people, no matter what their background, had the potential to avail themselves of this “marvellous power” of hard work, as long as they focused on expanding their minds through education. “The health and strength of the soul is of far more importance than is that of the body,” Douglass declared. “[T]here can be no independence without a large share of self-dependence, and this virtue cannot be bestowed. It must be developed from within.” … Douglass defined “self-made men” as those who have overcome obstacles to “build up worthy character,” those who are “indebted to themselves for themselves.” Rejecting the traditional view of the established Church—that “liberty and slavery, happiness and misery, were all bestowed or inflicted upon individual men by a divine hand and for all-wise purposes”—Douglass insisted that we are responsible for our own happiness and success. “Faith, in the absence of work, seems to be worth little, if anything,” he writes, in a crisp encapsulation of Franklin’s creed. He also rebuked the “growing tendency” to seek happiness through “sport and pleasure.” Douglass says that “real pleasure” can only be found in “useful work”—“in the house well built, in the farm well tilled, in the books well kept, in the page well written, in the thought well expressed, in all the improved conditions of life” all around us.

As explored in previous essays, Douglass’ sound advice contrasts starkly with modern and misnamed “progressive” approaches to life, which emphasize largely false narratives that focus largely on imagined external threats rather than internal self-empowerment. As Rosen writes:

In his speeches after the war, Douglass demanded nothing more and nothing less than the freedom for African Americans to pursue happiness. As early as 1865, in the speech “What the Black Man Wants,” Douglass said in response to the rhetorical question “‘What shall we do with the negro?’ I have had but one answer from the beginning. Do nothing with us!” All he asked, Douglass said, was “give him a chance to stand on his own legs! Let him alone!” In his “Self-Made Men” speech, Douglass used the same language. “I have been asked, ‘How will this theory affect the negro?’ and ‘What shall be done in his case?’ My general answer is ‘Give the negro fair play and let him alone. If he lives, well. If he dies, equally well. If he cannot stand up, let him fall down.’” For Douglass, the pursuit of happiness required equal opportunity for industrious work, so that all individuals could achieve their potential.

Frederick Douglass would have been appalled at the current state of public education, especially its disservice to lower-income students, including a disproportionate number of African-Americans. As Rosen writes:

In the end, Douglass believed that the solution to the violent passion of prejudice was the cool reason of education. In 1883 he called for a federal mandatory school attendance law [contrast that with the current crisis in absenteeism in public schools following the misguided school closures during the COVID pandemic] … Douglass explicitly connected equal opportunity for education with the pursuit of happiness. “To deny education to any people is one of the greatest crimes against human nature,” he maintained in a speech on “The Blessings of Liberty and Education.” “It is to deny them the means of freedom and the rightful pursuit of happiness, and to defeat the very end of their being. They can neither honor themselves nor their Creator.” Returning to the theme of intellectual freedom, which had launched his career as a free man, Douglass emphasized the indignity of prohibiting Black people from learning to read. By denying all people an equal opportunity for education, he reiterated, slavery inflicted wrongs even “deeper down and more terrible” than “the labors and the stripes”—namely, “mental and moral wrongs which enter into his claim for a slight measure of compensation.”

As Rosen writes, most school students today are being deprived of any exposure to the practical philosophies of life espoused by the Founders and their intellectual heirs such as Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln:

Like the Founders … [Justice] Ruth Bader Ginsburg received an education that included primary texts from classical, Enlightenment, and American history. Some Founders—such as Adams, Madison, and Hamilton—had to read and master these texts in order to graduate from college. Other great Americans, including Douglass and Lincoln, educated themselves by reading texts that they found, previously compiled and condensed, in the popular readers and handbooks of their time. Closer to our time, Justices Brandeis and Ginsburg were exposed to the classics through American public schools. (My mother, who graduated from a New York City public high school in 1950, the same year as Justice Ginsburg, received a similar education.) And yet, by the time I graduated from high school three decades later, these texts had largely fallen out of the curriculum. Why? One possible answer is that America’s understanding of the pursuit of happiness in popular culture was transformed in the 1960s and 1970s from being good to feeling good; from eudaimonia (the pursuit of virtue) to hedonia (the pursuit of pleasure). This was a stark departure from the understanding of previous generations. The change from a popular culture that rejected pleasure seeking to one that celebrated it marked a shift in our understanding of happiness as something that requires delayed rather than immediate gratification.

Rosen recounts the observations of Alexis de Tocqueville, the trenchant French observer of American life in the mid-nineteenth century, who even then realized that the unique freedom experienced in America would have to rely on a continued understanding of the classical virtues:

Tocqueville identified another, distinctively American idea that he hoped would persuade Americans to continue to avoid the pursuit of short-term pleasure and cultivate the self-mastery necessary for lifelong happiness. He called it “the doctrine of self-interest properly understood,” and it was the doctrine of the ancient Stoics, channeled through Benjamin Franklin. In a succinct summation of the classical understanding of the pursuit of happiness, Tocqueville wrote: “Philosophers teaching this doctrine tell men that, to be happy in this life, they must keep close watch upon their passions and keep control over their excesses, that they cannot obtain a lasting happiness unless they renounce a thousand ephemeral pleasures, and that, finally, they must continually control themselves in order to promote their own interests.” This doctrine by itself “could not make a man virtuous, but it does shape a host of law-abiding, sober, moderate, careful, and self-controlled citizens… through the imperceptible influence of habit.” For Tocqueville, as for Franklin, these habits of self-mastery, self-control, and delayed gratification would allow citizens to pursue their long-term interests rather than short-term pleasures. But how could Americans be persuaded to pursue happiness through the habits of self-mastery, or “self-interest properly understood,” as the orthodoxies of traditional religions began to be questioned by science in the nineteenth century? Tocqueville’s answer was character education … In the nineteenth century … the task of bringing the classical understanding of the pursuit of happiness to American students on a wide scale fell to textbook writers. A standard nineteenth-century law school textbook includes, in its section on moral philosophy, most of the books on Jefferson’s reading list, including Cicero, Seneca, Xenophon, Locke, and Reid, as well as a prayer from Samuel Johnson and a Franklin-like list of practical virtues for daily living. As for public school students, the most important influence on their nineteenth-century curriculum was Horace Mann. A Massachusetts abolitionist, school reformer, and associate of Emerson and John Quincy Adams, Mann became known as the founder of American public schools. “No one did more than he to establish in the minds of the American people the conception that education should be universal, non-sectarian, and free,” the educational historian Ellwood Cubberley wrote in 1919, “and that its aim should be social efficiency, civic virtue, and character.” Mann argued that teachers should be trained in moral education and give students an opportunity to practice virtues like kindliness, self-discipline, and self-control in the classroom. In particular, Mann stressed the importance of daily reading about moral exemplars throughout history. Even fifteen minutes a day, he stressed, would inspire habits of self-mastery and good citizenship. “Let a child read and understand such stories as the friendship of Damon and Pythias, the integrity of Aristides, the fidelity of Regulus, the purity of Washington, the invincible perseverance of Franklin,” he declared, “and he will think differently and act differently all the days of his remaining life.” Mann’s approach to character education persisted in American public schools from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century. And for most of that period, the self-help textbook for self-made boys and girls across America was the McGuffey Reader, a primer that sold more than 120 million copies between 1837 and 1960. Like the Columbian Orator, which inspired Lincoln and Douglass, the McGuffey readers were full of Bible verses and hymns, although they became increasingly secularized. They began publication around the time Henry Clay coined the phrase “self-made man” and promised that students who practiced Ben Franklin’s thirteen virtues, as well as more explicitly Christian ones, could be assured of following Franklin’s path from rags to riches. They included homilies on industry (“[W]ork, work my boy, be not afraid; look labor boldly in the face; Take up the hammer or the spade, and blush not for your humble place”) and the power of perseverance over inherited genius (“Thus plain, plodding people, who often shall find, Will leave hasty, confident people behind”). The McGuffey Reader was the standard moral philosophy text for many generations of public school students; but it came to be seen, by the 1960s, as anachronistic.

Further, Rosen writes, the former norm of character education came into disrepute just as the modern science of well-being was vindicating it:

[While] the Supreme Court … stressed that it was permissible to read religious texts as part of secular courses about history, ethics, and literature, many public schools responded by removing texts that mentioned God in any way. Partly as a result, the McGuffey Reader dropped out of the public school curriculum in the mid-twentieth century … [But] as pop culture was rejecting the Stoics’ ancient wisdom, however, new insights from social and behavioral psychology confirmed it. In 1990 the social psychologists John Mayer and Peter Salovey explored the skills necessary for “emotional intelligence,” which they defined as “the subset of social intelligence that involves the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions.” Emotional intelligence turned out to be another name for Aristotle’s eudaimonia, or human flourishing through emotional self-regulation. The new term was popularized by the psychologist Daniel Goleman, whose 1995 best seller identified four components of emotional intelligence: “self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and the ability to manage relationships.” Key to the idea of emotional intelligence is the classical idea about the importance of balancing reason and emotion so that we can achieve a productive harmony. “[F]eelings are essential to thought, thought to feeling,” Goleman writes, quoting the Renaissance humanist Erasmus. “But when passions surge the balance tips: it is the emotional mind that captures the upper hand, swamping the rational mind.” For Goleman, as for the ancient philosophers, emotional intelligence includes “emotional self-regulation,” or “the ability to deny impulse in the service of a goal.”38 Psychologists have confirmed that skills of impulse control, which start to build from infancy, are, in fact, crucial to adult happiness. The Israeli psychologist Reuven Bar-On studied the relationship between emotional intelligence and self-actualization, or the fulfillment of human potential. He found that “emotional intelligence is highly associated with happiness,” including “the quest for meaning in life.” “If, as Aristotle and the Humanistic psychologists claim, fulfillment and actualization are happiness, and if, as it appears, emotional intelligence is a refinement of Aristotle’s concept of virtue,” Samuel Franklin writes in The Psychology of Happiness, then new insights from social psychology confirm the ancient wisdom. In other words, emotional self-regulation does, in fact, allow us to fulfill our potential, leading to long-term happiness. At the same time that social psychologists were confirming Aristotle’s insights about how emotional self-regulation leads to happiness, cognitive behavior psychologists were confirming Cicero’s and Epictetus’s insights about how tempering our thoughts can reduce anxiety and depression. Drawing on the ancient wisdom that reason could be used to calm the “perturbations of the mind,” cognitive behavior therapists found that examining our thoughts can help us discard the “cognitive distortions” that contribute to depression and anxiety. “The philosophical origins of cognitive therapy can be traced back to Stoic philosophers, particularly Zeno of Citrium (fourth century BC), Chrysippus, Cicero, Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius,” wrote Dr. Aaron Beck, the founder of cognitive therapy in 1979. “Like Stoicism, Eastern philosophies such as Taoism and Buddhism have emphasized that human emotions are based on ideas. Control of most intense feelings may be achieved by changing one’s ideas.” Cognitive behavior therapy identifies a series of “cognitive distortions”—namely, unproductive thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes—that can lead to anxiety and depression. As summarized by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt in The Coddling of the American Mind, the cognitive distortions include mind reading, fortune telling, catastrophizing, labeling, discounting positives, shoulds, blaming, unfair comparisons, and “emotional reasoning,” where “you let your feelings guide your interpretation of reality.” And cognitive behavior therapy itself is a practical way of using reason to regulate emotions, which the Founders would call passion.

But then, as Rosen writes:

[T]hen came social media. Soon after cognitive behavioral therapy resurrected the ancient wisdom about how to address anxiety and depression through reasoned self-reflection, Facebook, Twitter, and smartphones exploded on the scene. As Lukianoff and Haidt also note, after the iPhone was introduced in 2007, social media platforms began addicting Americans in large numbers, beginning in middle school. Facebook was founded in 2004, Twitter in 2006, Tumblr in 2007, Instagram in 2010, and Snapchat in 2011. Between 2011 and 2016, rates of depression among adolescents began to rise, and the social psychologist Jean Twenge argues that the main cause of the teenage mental health crisis that began around 2011 is the spread of social media and smartphones. In her book iGen, Twenge found that two activities involving screens are highly correlated with depression and suicide: electronic devices (including smartphones, tablets, and computers) and watching TV. By contrast, time spent on five nonscreen activities have an inverse relationship with depression: sports, attending religious services, in-person social interactions, doing homework, and reading books and other print media. The Founders would not have been surprised that heavy use of social media increases anxiety and decreases happiness. Their neo-Stoic understanding of emotional intelligence emphasized the importance of deliberation and thinking before you speak; social media rewards immediate responses and tweeting before you think. The Founders counseled moderation in speech; social media rewards extremism. The Founders urged the need to think for yourself and form opinions without seeking the approval of the crowd; on social media, popular approval—in the form of likes, retweets, and shares—is the only currency. The Founders insisted that happiness and good citizenship require that we moderate our unproductive emotions, such as anger and envy; social media encourages us to share those emotions as widely as possible. But if our cell phones and screens represent the Founders’ nightmare, they also offer a potential benefit. The most striking difference between the daily schedules of the Founders and our schedules today is how much time they spent reading books. It’s inspiring to see the carefully regimented hourly reading schedules that Franklin and Jefferson, John and John Quincy Adams, Lincoln and Douglass set for themselves as young men, and how vigilantly they continued their voracious daily reading for their entire lives. (As John Adams told his son, you are never alone with a poet in your pocket.) Their challenge was access to books—think of how devastated Frederick Douglass was when his enslavers forbade him to learn to read, or how excited Adams was when he learned that ancient Hindu texts had survived the destruction of the library at Alexandria. As a young boy, Lincoln borrowed a copy of Parson Weems’s Life of George Washington from a local farmer and then accidentally ruined it by leaving it out in the rain. When he returned the soaked book and explained what had happened, the farmer made him pull corn for two days in order to repay his debt. In the Founders’ time, books were scarce, and access to them precious. Today, by contrast, the miracle of the Internet has given us access to all the surviving texts published since the dawn of time—on our cell phones and tablets, wherever we are, at every moment of the day, often free of charge. When I was young, I remember visiting the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, with my mother for the first time. As I stood in the Great Hall of the magnificent Thomas Jefferson Building, I was filled with wonder at the thought that all the books in the world could be found in one place. Only a few decades later, for the first time in human history, we carry in our pockets all the wisdom of the ages, including the complete works of the ancient thinkers who inspired the Founders and actual copies of the books and editions that the Founders themselves read. All we need is the self-discipline to take the time to read them. Here the Founders themselves are an inspiration. As their example shows, it helps to set aside dedicated time every day for deep reading rather than idle browsing and sharing. “I have given up newspapers in exchange for Tacitus and Thucydides, for Newton and Euclid,” Jefferson wrote to Adams, “and I find myself much the happier.”

Rosen concludes with this note, and this appendix, which I reproduce here:

In the hope that you may be inspired by the Founders’ reading habits to read or listen to the books that shaped their pursuit of the good life, I’ve included the Founders’ reading list in the appendix. There’s a vast library of wisdom waiting to inspire us every day to learn and grow. Happy reading!

Most Cited Books on Happiness from the Founding Era

1. Cicero, Tusculan Disputations and On Duties Grieving the death of his daughter Tulia, in 45 BC, the Roman statesman Cicero retired to his country villa in Tusculum, where he consoled himself with the study of philosophy. The result of his studies was Tusculan Disputations, a meditation on death, pain, grief, passion, and virtue and a classic text of the Stoic school. Franklin chose a quotation from it as the motto for his self-project and Jefferson, who read it for consolation after the death of his father, cited it as the source of his understanding of the pursuit of happiness. It was also a favorite of John Adams and John Quincy Adams, who adopted a quotation from the book as his personal motto. One year after Tulia’s death, Cicero wrote On Duties, a treatise on the good life, which also strongly influenced the Founders. The English philosopher John Locke said that anyone who read only two books—the Bible and On Duties—could attain a complete moral education in “the principles and precepts of virtue, for the conduct of his life.”

2. Marcus Aurelius, Meditations As the sixteenth Emperor of Rome, Marcus Aurelius faced wars on the frontier, a revolt within the Roman army, and the death of his wife in AD 175. To compose his emotions, he wrote about Stoicism in a private diary, which became known as the Meditations. It particularly influenced George Washington and John Quincy Adams, who told his father that Marcus “guards us most carefully against [life’s] prosperities.”

3. Seneca’s Essays Like Cicero and Marcus Aurelius, Seneca the Younger was a Roman statesman and Stoic. Exiled from Rome to Corsica in AD 41 after being accused (probably falsely) of an affair with the niece of the emperor Claudius, Seneca spent his time writing Stoic essays, letters, and dialogues. Later, he became an advisor to the emperor Nero who ordered him to commit suicide, which he did, stoically. As they experienced the shifting fortunes of politics and life, Founders including Franklin, Jefferson, and Adams turned to Seneca to maintain fortitude and tranquility. Washington read Seneca’s essays on anger, courage, and retirement, and Abigail Adams cited Seneca to advocate for women’s equality.

4. Epictetus’s Enchiridion Epictetus was another ancient Stoic philosopher, but unlike Cicero, Marcus, and Seneca, he was Greek and born into slavery. Disabled because of abuse he had endured from his master, Epictetus originated Stoicism’s famous “dichotomy of control,” which urges us to focus on what is in our control (our own thoughts and actions) rather than what is external to us (wealth, fame, and fortune). His Enchiridion, or Handbook, is a compilation of his precepts, and he influenced both John and Abigail Adams and their son John Quincy, who wrote that Epictetus “prepares us most effectually for the evils of life.”

5. Plutarch’s Lives Plutarch, the most frequently cited classical author in the founding era, was a Roman biographer and essayist. His Lives are short biographies of eminent Greeks and Romans. Plutarch was especially interested in the character and motives of his subjects, and his Lives are filled with stories of virtue, honor, and heroism as well as vice, ambition, and defeat. Franklin and Jefferson found Plutarch’s portrait of Cicero especially illuminating, while Hamilton and Madison focused on his biography of the Spartan lawgiver Lycurgus, which they both cited in The Federalist Papers. Hamilton also enjoyed Plutarch’s account of Sparta’s nude parades, and one of Plutarch’s essays inspired Franklin to experiment with vegetarianism.

6. Xenophon’s Memorabilia of Socrates A Greek philosopher and (along with Plato) student of Socrates, Xenophon in his Memorabilia provides an account of Socrates’s life and teachings. Franklin was especially influenced by the Memorabilia, and the book’s vivid description of the myth of Hercules’s choice between Vice and Virtue was one of Adams’s favorites—though it also caused him to have at least one nightmare.

7. Hume’s Essays In his essays and treatises, English philosopher David Hume expounded on topics both personal and political, from economics to virtue to the nature of knowledge itself. He used the phrase “pursuit of happiness” twice. He was also one of the most-discussed philosophers of the Constitutional Convention and influenced Madison’s discussion of factions in “Federalist No. 10.”

8. Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws The political treatise of the French judge and philosopher Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws was the single most-cited book of the founding era and convinced the Founders of the need for separation of powers to avoid tyranny and despotism. In “Federalist No. 47,” Madison called him “the celebrated Montesquieu,” paying homage to his influence on the Constitution’s system of checks and balances. Hamilton read Montesquieu when he was a student at Columbia, and Adams once had a dream in which the figure of Virtue admonished him to read more Montesquieu.

9. Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding and Treatises on Government The most influential and frequently cited English philosopher for the founding generation, John Locke was famous for his theories about the social contract that individuals make when they form governments and about the mind as a blank slate, or tabula rasa. Along with Cicero, Aristotle, and Algernon Sidney, he was one of the four authors that Jefferson said most influenced the Declaration, and along with Francis Bacon and Isaac Newton, Locke was one of “the three greatest men that have ever lived, without any exception,” in Jefferson’s words. Among the other Founders who read him were Wilson, Hamilton, and Madison. His use of the phrase “the pursuit of happiness” occurs not in his Two Treatises but in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.

10. Adam Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments The Scottish philosopher Adam Smith eventually became world-renowned for his Wealth of Nations, which described the emerging system of capitalism, but to the Founders, Smith’s first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, was equally important. In it, Smith described how passions influenced our actions. It was read by both the elder and younger Adams, among others.

Now, how prevalent are the classical virtues — and the practical principles of productivity and happiness espoused by the Founders — today?

When asked which qualities are the most important to teach children, those who were “consistently conservative” answered “being responsible” and “hard work” more often than the average American. Those who were “consistently liberal” answered “being responsible” and “hard work” less often than the average American.

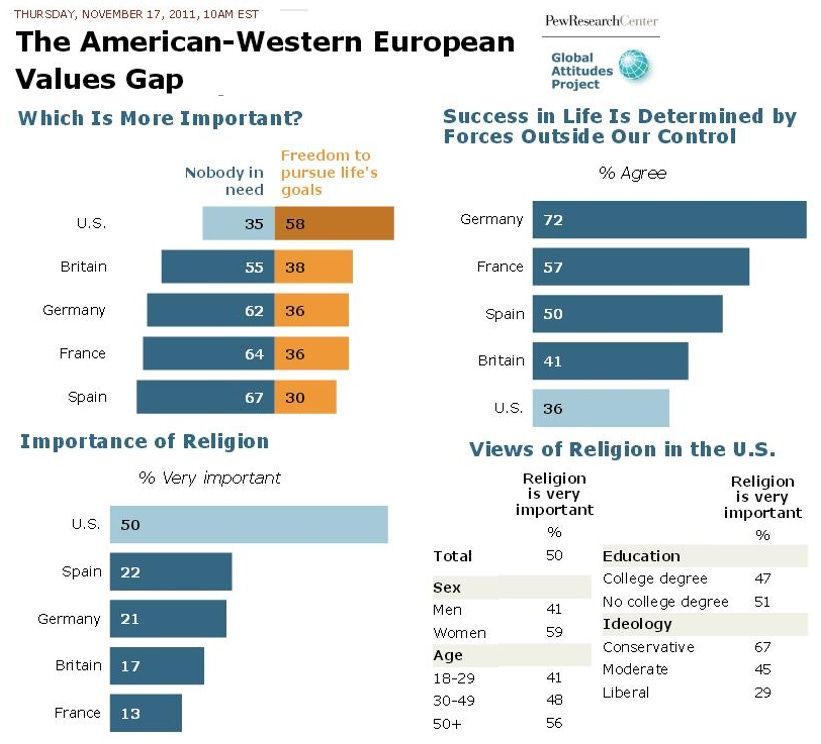

Americans continue to remain exceptional worldwide (at least as of 2011, when this survey was published) in that they place more importance on freedom to pursue life’s goals, are more likely to think success is determined by individual initiative, and that religion is very important.

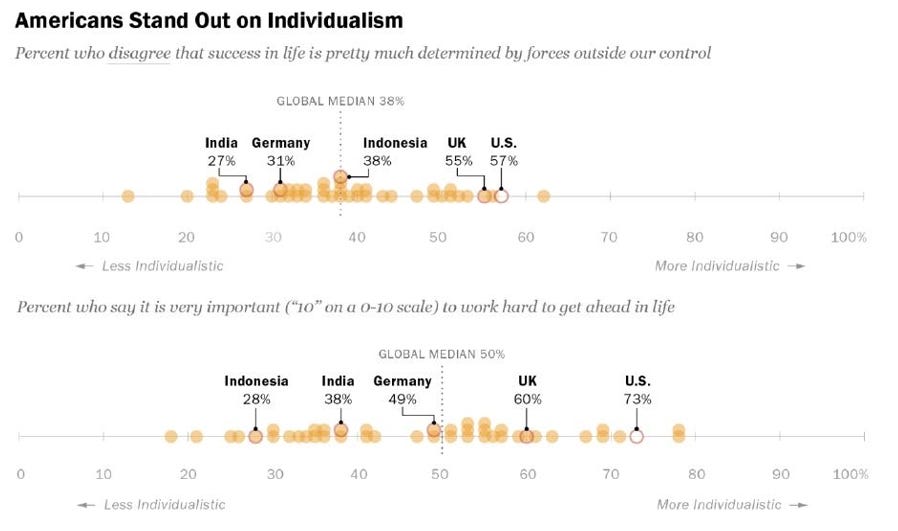

According to a Pew survey from 2015, Americans also stand out worldwide for their understanding that success in life is largely a result of individual initiative.

And as Frederick Hess and R.J. Martin point out:

If one asks parents — of any race — what values they want their kids to learn, more than four out of five will similarly name concepts like “hard work,” “being well-mannered,” and “being responsible.” In fact, black parents are one to three percent more likely than white parents to think traits like “hard work,” “being well-mannered,” and “persistence” are “important to teach children.” … The idea that Christianity belongs to white culture could come as a surprise to the 72 percent of black Americans who identify as Christian, especially when only 65 percent of white Americans do so. The idea that timeliness and objectivity are the province of white culture would probably come as a surprise to air traffic controllers or cardiovascular surgeons in Cambodia and Cameroon, as it turns out that these traits are crucial to their professional competence and success — whatever the practitioner’s race or culture. While it might be tempting to laugh off the Smithsonian’s chart as political correctness run amok, that would be a mistake. The troubling conviction that admirable, useful, universal values like hard work and politeness are somehow the product of “white supremacy” has been gaining increasing currency in education circles. Just this month, the influential KIPP charter network announced it was abolishing its motto “Work Hard. Be Nice.” as part of its push to “dismantle systemic racism.”

This concludes this essay series on a Constitution to control government, drafted by people who controlled their emotions. Has modern science tended to vindicate the views of the Founders regarding the best mental path to happiness? That will be the subject of our next essay series.